Author: Mr.Yu

Someone told us that their favorite car brand has not been as good in recent years because it has taken the “detour” of intelligence. Some even bluntly say that it is all Tesla’s fault. Indeed, besides new energy and assisted driving, Tesla’s biggest shock to the world is probably its “tech sense”.

Look at the entire screen, it can almost achieve everything you want on a car. Physical buttons? Let them all go to hell! The myriad of buttons can be replaced by my Model 3’s touch screen.

“Tech sense” has indeed increased, but physical buttons, which are the most familiar things in a car, have also disappeared.

More interestingly, this “elimination of physical buttons” in cockpit design is being recognized by more and more car companies. As the familiar physical buttons become less and less, or even disappear in various new car cockpits, many people believe that this marks the coming of the era of intelligence.

However, let’s think about it for a moment, is this really a good thing to do?

GeekCar, as a media that deeply studies intelligent car cockpit interaction, has established its own intelligent cockpit evaluation system. Based on this constantly evolving system, GeekCar conducted a detailed evaluation of market models. In addition to the evaluation results, we also have our own opinions.

Today, we want to talk to you about why we think that completely getting rid of all physical buttons in the car is unreliable in the current scenario.

Why has touchscreen become a hot cake?

First, let’s clarify one point: for today’s cars, touch screen-based in-car interaction has its advantages, and it has brought a new dimension to product competitiveness. This is also why today’s car manufacturers are so keen on stuffing one, two or even four or five screens into the car in every way possible.

First, the amount of information that can be carried. We are now very accustomed to interacting with digital interfaces, including but not limited to mobile phones, tablets, computers, electronic information screens in commercial places, and self-service ordering screens in fast food restaurants. With more and more technologies being decentralized and mass produced, functions such as assisted driving, real-time navigation, and cockpit entertainment are gradually being introduced. We cannot cram every physical button corresponding to each function into the inch-sized space of the car interior, like the cockpit of an airplane that accommodates hundreds of buttons, levers, scales, and gauges. The amount of information that networked digital interfaces can carry far exceeds that of physical buttons with preset functions.

Secondly, the enhancement of technology sense. The term “technology sense” may sound vague, and its application on products is a matter of personal preference. Nevertheless, most people with knowledge and experience in technology can feel it. Apart from mobile phones, who doesn’t own several tablets, smartwatches or TWS earphones nowadays? This phenomenon drives the rapid iteration of digital products, empowered by the upgrade of technology instead of being a trap of consumerism. According to IDC’s data, the global sales of smartphones surged from 8.2 million units to 1.301 billion units between 2006 and 2014. During those years, consumers’ willingness to adopt smart products increased rapidly. Just as e-ticketing in smartphones and wearable devices has widely replaced paper tickets for public transportation in a short span, digital devices can perform more and more tasks. Therefore, we cannot perceive the new attributes of devices with an outdated perspective.

Secondly, the enhancement of technology sense. The term “technology sense” may sound vague, and its application on products is a matter of personal preference. Nevertheless, most people with knowledge and experience in technology can feel it. Apart from mobile phones, who doesn’t own several tablets, smartwatches or TWS earphones nowadays? This phenomenon drives the rapid iteration of digital products, empowered by the upgrade of technology instead of being a trap of consumerism. According to IDC’s data, the global sales of smartphones surged from 8.2 million units to 1.301 billion units between 2006 and 2014. During those years, consumers’ willingness to adopt smart products increased rapidly. Just as e-ticketing in smartphones and wearable devices has widely replaced paper tickets for public transportation in a short span, digital devices can perform more and more tasks. Therefore, we cannot perceive the new attributes of devices with an outdated perspective.

Thirdly, the role played by in-car screens has changed drastically. We are not discussing here the diversity of styling or the difference between LCD, Mini-LED, and OLED but the role played by screens in cars. In-car screens are not recent inventions.

In 1979, the Aston Martin Lagonda Series 2 was the first car to use an analogue system to simulate performances, such as engine speed, vehicle speed, and others, apart from displaying dashboard information.

In 1987, the Toyota Crown, a luxury car model designed exclusively for the Japanese market, was equipped with a CD-based navigation system, which provided a colour display. The top model of the Crown, the Royal Saloon version (the real luxury version), with the MS137 onboard computer, relied on a dead reckoning algorithm for navigation. Although its accuracy was doubtful, compared to today’s navigation systems, it was still considered a technological breakthrough at that time.

Today, behind the hardware innovation lies the ever-increasing power of software that cannot be ignored. While the hardware lays the foundation of the user experience, the system and software determine the upper limit of the user experience.Fourthly, high scalability. For the majority of the time since its birth, automobiles have been regarded as tools for transportation, with only single functions and limited scenes. As mentioned earlier, safety is the core of driving and drivers’ attention needs to be focused on driving behavior. In recent decades, we have seen the continuous extension of entertainment functions in vehicles, such as navigation, music, audio content, and videos. However, current offerings are not enough to satisfy car manufacturers’ appetite. On the other hand, more and more ecosystems, application markets, and even games have also been introduced into cars. While Musk has declared that he wants to bring Steam and various 3A games to Tesla, GAC has already set up King of Fighters with wireless gamepad connected to its Aion series.

Fifthly, changes in users’ level of participation in driving. As the intelligence level of vehicles continues to increase, users are no longer just concerned with vehicle safety, driving performance, and comfort. The vehicle-mounted screen can efficiently transmit real-time information about the vehicle and the road to the cockpit, enabling drivers to make rational decisions and reactions quickly. By presenting the vehicle status and settings in a digital interface, users are able to participate in more and finer vehicle settings. These are unmatched by the era when the car’s in-car control only had mechanical instruments and buttons.

In this way, each car on the road is like an information island. Even with the commonly used combination of mobile phones and car-mounted holders, we can only achieve the connection between people and the network while driving, besides navigation, music play, and phone calls, and we cannot expect more.

Safety is still the most essential element and the basis for all behaviors while driving. The design and optimization of the mobile phone operating system and application interface are not for driving use. Therefore, it is not practical to keep staring at the mobile phone as usual, at least not until L4 or higher levels of automatic driving are realized.

After networking, more information flows between vehicles and people. The fundamental difference between screens and physical buttons is that the in-car screen acts as both an information output device and an information input interface.

So the conclusion of this stage is: the vehicle-mounted screen is a must for the development of intelligent vehicles.

However, despite all that has been said, has the physical button in the car really completed its historical mission and been destined to be completely replaced by the touch screen? Our conclusion is: not yet.There is a point that needs to be clarified: many people say that smart cars are just putting an iPad in the car cockpit.

This statement is irresponsible. The interaction between car interiors and digital products is completely different. As we mentioned earlier, before L4 level autonomy is fully achieved, safety and efficiency are still the core of car interior interaction.

If you stare at the in-car screen for a long time interacting without stopping while driving, what is the essential difference between this and using a mobile phone while driving that is explicitly prohibited in the Road Traffic Safety Law?

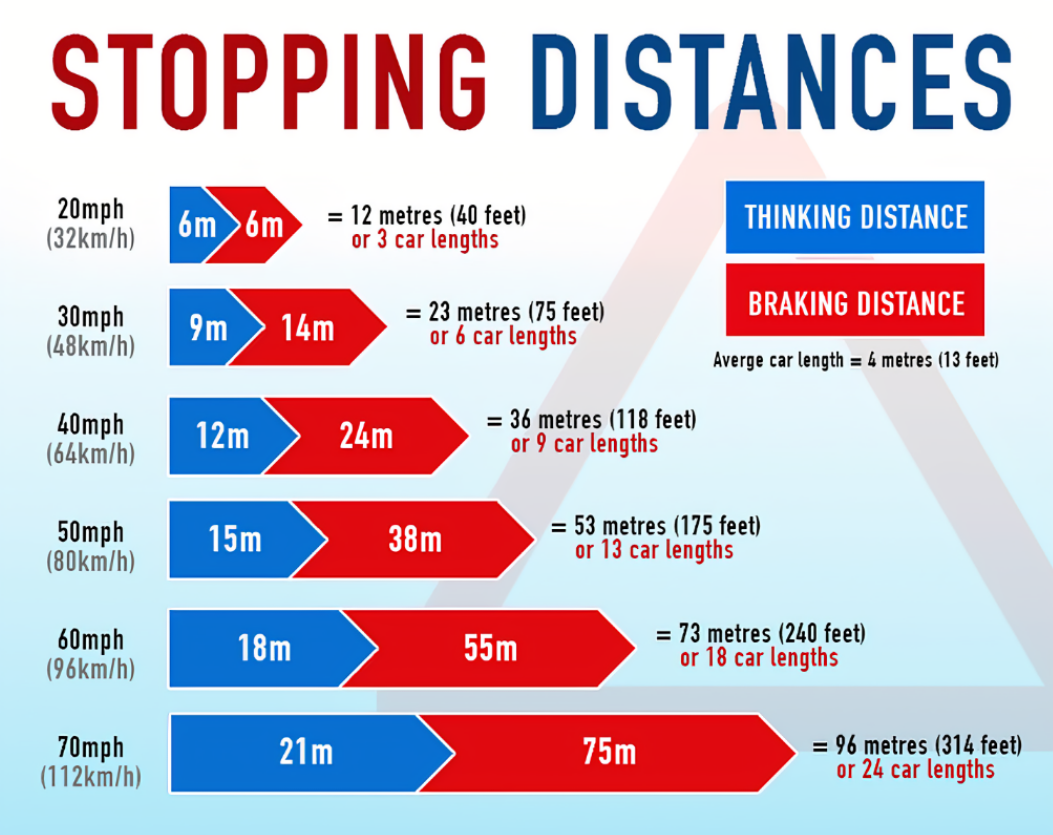

Let’s do a simple calculation roughly. For the car driving at a constant speed of 80 kilometers per hour, the distance traveled per second is about 22 meters. When the car runs at this speed, its mechanical braking distance is close to 30 meters. The entire braking process includes: danger-identification-decision-making-operation of the braking device (brake)-start of the brake device-stop of the vehicle. The first four steps of the whole process usually leave drivers with only a fraction of a second for reaction time, any attention shift could turn into an accident.

From this perspective, not only the work deadlines, but also the momentary distraction during frequent interactions could put an end to the drivers’ lives.

If the screen has so many advantages, why do we still need physical buttons?

In the current national standard “Technical Specifications for the Safe Operation of Motor Vehicles” (GB 7258-2017), there are no specific requirements for which buttons must exist in the car cabin. We believe that some physical buttons in the car interior still need to be retained.

The first thing that comes to mind is the high-frequency buttons in the car. The concept of “high frequency” not only corresponds to a high frequency of use but also a very high requirement for accurate operation, such as the most commonly-used adjustment of the volume, air conditioning, and ADAS.

Since we repeatedly emphasize that safety is the top priority in interaction scenarios, then how to measure attention diversion? We believe that the representative visual behavioral expression is eye-tracking deviation. Broadly speaking, the longer the eye-tracking deviation time during operation, the lower the safety factor.

Let’s take a typical example of a buttonless scenario.

In GeekCar’s programs “Intelligence Cockpit Intelligence Bureau” and “Is Your Intelligent Cockpit Easy to Use?”, we have reviewed the “Dad God Car” Ideal ONE and accumulated a significant degree of understanding.

There are a total of 4 screens in the Ideal ONE cockpit: instrument panel, multimedia screen, co-driver entertainment screen, and vehicle control screen. The interaction modes that the driver will use while driving are: voice interaction, screen touch, and multi-functional button interaction on the steering wheel.

In the HMI experience measurement regarding human-machine interaction testing, we notice a characteristic feature of the ideal ONE car machine system: blind adjustment of air conditioning temperature and wind volume. Specifically, by sliding up and down in the middle of the car control screen, the air conditioning temperature can be adjusted, while sliding left and right corresponds to adjusting the air conditioning wind volume.

When we set the task of “adjusting the air conditioning temperature to 23 degrees Celsius” and mark several special positions in the cabin, combined with eye-tracking equipment to measure three indicators: task completion time of 6.24 seconds, total glance time of 4.21 seconds, and a single glance time of 1.95 seconds.

After bringing the time of the three indicators into the fitting curve, we get the scores of each indicator: task completion efficiency is 73.60 points (higher than 73.6% of tasks on the market), car machine single glance time is 63.02 points (higher than 63.02% of tasks on the market), and total glance time is 64.94 points (higher than 64.94% of tasks on the market).

Finally, we obtain a score of 66.48 points for the task of “adjusting the air conditioning temperature”, and the test result indicates cautious operation.

Although the ideal ONE is equipped with a blind adjustment function for air conditioning temperature, based on the test process and results, blindly operating the air conditioning temperature and wind volume is not that easy. There are several issues:

Issue 1, Need to glance at the non-button area on the car control screen. The screen layout is shaped like a “return” character, and the temperature adjustment cannot be made in the functional icon area around the screen. This means that when users want to use blind manipulation, they need to lower their heads to glance at the car control screen, confirm the non-button area where they can adjust the temperature before they can adjust the temperature.

Issue 2, Difficult to adjust precisely. When users perform vertical sliding operations, the air conditioning value also changes “smoothly”, making it difficult to accurately adjust to the desired temperature value. Users tend to adjust it too much or too little, requiring repeated sliding to make corrections, which causes users to stare at the instrument panel for a certain period of time. If blind manipulation gestures are added with sound and vibration feedback or combined with AR-HUD to display the temperature on the front windshield, perhaps users can adjust the temperature precisely without staring at the instrument panel.

Now let’s take a look at another typical problem.During the HMI experience measurement test of XPeng P7, we noticed that the air conditioning quick adjustment button was placed in the middle of the sidebar, with intuitive values and an obvious driver bias in its design. However, the icons on the sidebar are generally small, with a dense arrangement and no clear separation, which obviously affects the convenience of operation. If you encounter a bumpy road, accurate operation of the icons with your fingers may require careful aiming.

Note that this is not an isolated case. Such problems are also common on some infotainment screens that are not large, such as 8 to 9-inch car machines.

When we compared the evaluation results of multiple new forces and car models from traditional car companies based on the same task system, the results were surprising.

When it comes to common operations in the car such as adjusting the air conditioning wind speed and temperature, the models that retain quick physical buttons can achieve the desired result with the lowest attention expenditure.

For non-high-frequency but important functions such as unlocking the trunk and switching vehicle driving modes, we believe that relying on physical buttons to achieve them is better than operating the infotainment interface.

The reason is simple, well-designed physical button feedback is the guarantee of operational hand-feel. In terms of meeting hand-feel requirements such as operation touch, delay, and pressure, virtual buttons have no advantages. By analogy, it’s like many players of console games and computer games ridiculing mobile game players who hold their phones and play games as “rubbing glass.”

On the other hand, not all users compromise when faced with the terrible touch of virtual buttons.

In Japan, some users install third-party buttons on Tesla’s infotainment screen, which were developed by peripheral manufacturers to enhance the touch of phones/tablets games, to solve this problem. After all, with real tactile feedback, it is closer to the familiar way of operation.

When it comes to the biggest advantage of physical buttons, besides the personal preference and OCD of hand-feel, it is probably that the operation becomes visualized after forming muscle memory.

Huawei has tried to replace high-frequency physical buttons with virtual ones on its own phones.# Huawei Mate 30 Pro’s Volume Control Innovation

In September 2019, Huawei launched its Mate 30 Pro smartphone with a “super-curved OLED surround screen” with a stunning curvature of 88° on the side screens. However, the usual volume +/- keys on the left side of the phone were missing. Instead, users can quickly double-tap the side frames on the left and right sides of the screen to call up the volume control shortcut.

This feature relies mainly on the user’s finger pressing the top and bottom edges of the screen to adjust the volume. When the virtual slider moves up and down, there is significant vibration nearby to enhance the user’s sense of touch.

During my one year of normal use of this phone, I could clearly feel that the reaction speed of this design was fast, and the delay could be ignored. The efficiency was also not low, fully capable of meeting daily operations – except for situations that require quick muting, which can still be a bit awkward.

I still have to say that the traditional physical button method to control the volume is more in line with habits and intuition than this type of innovative design. For example, in some cases, when we need to confirm that the phone is muted, we only need to remember to hold down the volume button and keep it pressed, without having to take out the phone and occupy vision and attention to complete the operation.

But let’s get back to the topic at hand.

In fact, from the trend of in-car interaction, the design engineers of car companies have made many explorations to avoid relying on physical buttons to accomplish common functions. However, we must also admit that the position of physical buttons in in-car interaction, especially when it comes to driving safety, is still irreplaceable until more stable and reliable new interactive methods are available.

The industry is still working hard while the revolution is not yet successful

Of course, as we mentioned at the beginning, the trend of reducing physical buttons in cars is becoming more and more popular. While automakers are busy “killing off” physical buttons, they have not forgotten to make interactions evolve towards more user-friendly directions.

For example, the NIUTRON FREEDOM NV model of NIU Innovation has installed six linear micro-motion motors under its own 15.6-inch central floating screen. When users operate the screen, the micro-motion motors in the screen vibrate in various ways to transmit tactile feedback to users.

In the 2021 Mercedes-Benz S-Class sedan, which appeared in the “Intelligent Cockpit Intelligence Bureau” column last year, haptic feedback design was also introduced. When users operate the 12.8-inch OLED screen longitudinally, the screen will provide just-right vibration feedback.

In the 2021 Mercedes-Benz S-Class sedan, which appeared in the “Intelligent Cockpit Intelligence Bureau” column last year, haptic feedback design was also introduced. When users operate the 12.8-inch OLED screen longitudinally, the screen will provide just-right vibration feedback.

In the past two months, Ideal L9, which has aroused industry’s interest by continuously using several images to tease the market, also announced the existence of a 3D TOF (Time of Flight) sensor in the cabin during the first teaser. This means that gesture recognition and somatosensory interaction may also be included in the actual use of Ideal L9. As to whether the supplier behind it will be a Tier 1 company like Continental, Visteon or Delphi, or a promising start-up like Jifang Technology, Weidong Technology, etc., it still remains quite mysterious.

The exploration of interaction in the industry has never stopped. How can we deny the possibility just based on individual stereotypes?

Finally, let’s go back to the original point of this discussion: Since “making screen interaction as easy to use as physical buttons” is so difficult to achieve at this stage, why do automakers still want to completely “get rid of” physical buttons?

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.