I want to write an overview about the game between battery companies and car companies.

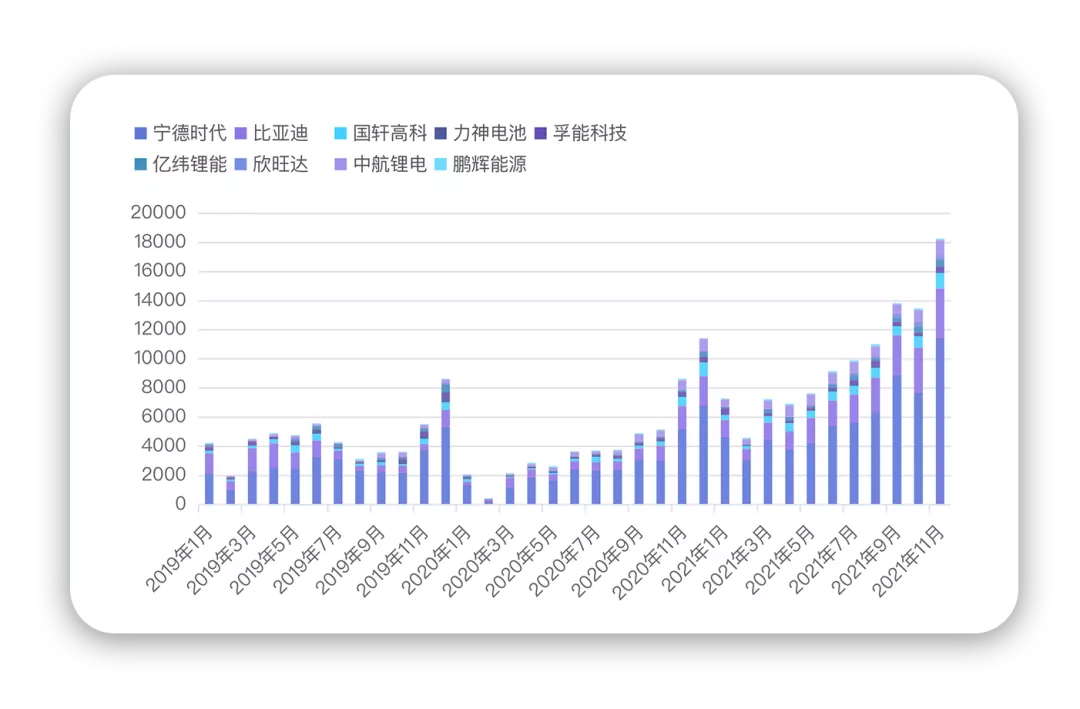

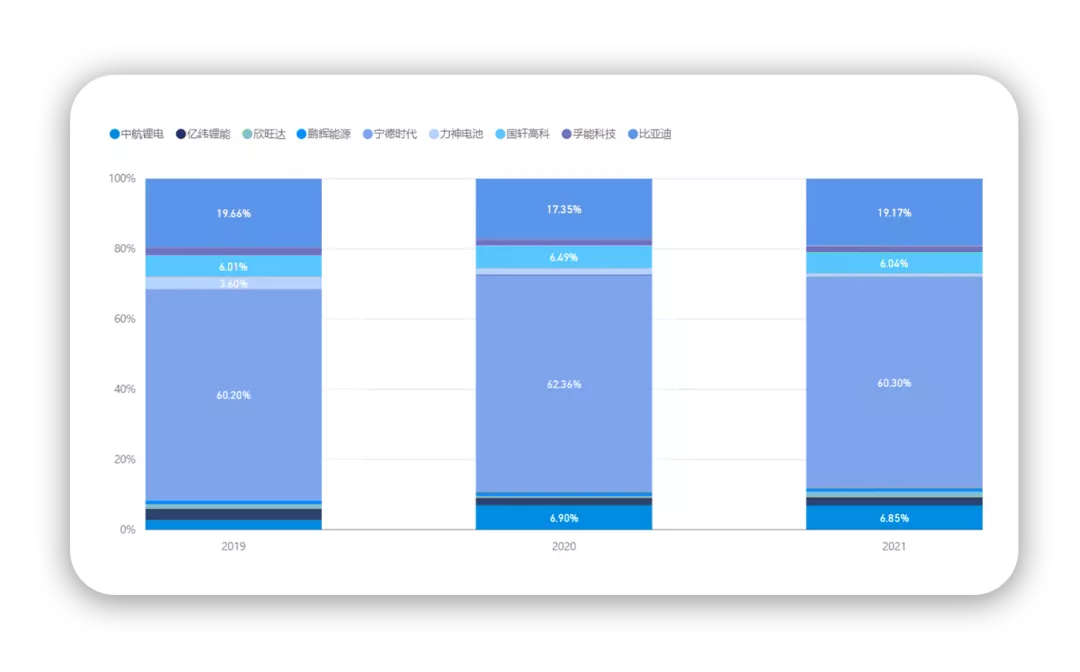

If we look at the timeline, the pattern of China’s power battery supply is shown in Figure 1 below:

-

The bargaining power of head battery companies over car companies is getting stronger, meaning that the head battery companies can increasingly drive production capacity and allocate output according to their own capacity distribution.

-

The entry threshold for second-tier companies to keep up is getting higher. Currently, BYD is expanding capacity. Due to the existence of many PHEVs, it has gradually climbed to the second tier with a monthly output of 1GWh. The ones following have an output of 300-400MWh.

I think we should focus on how second-tier battery companies can break through. Today’s first article will still be about BYD, and then expand to CATL, EVE Energy, and SVOLT.

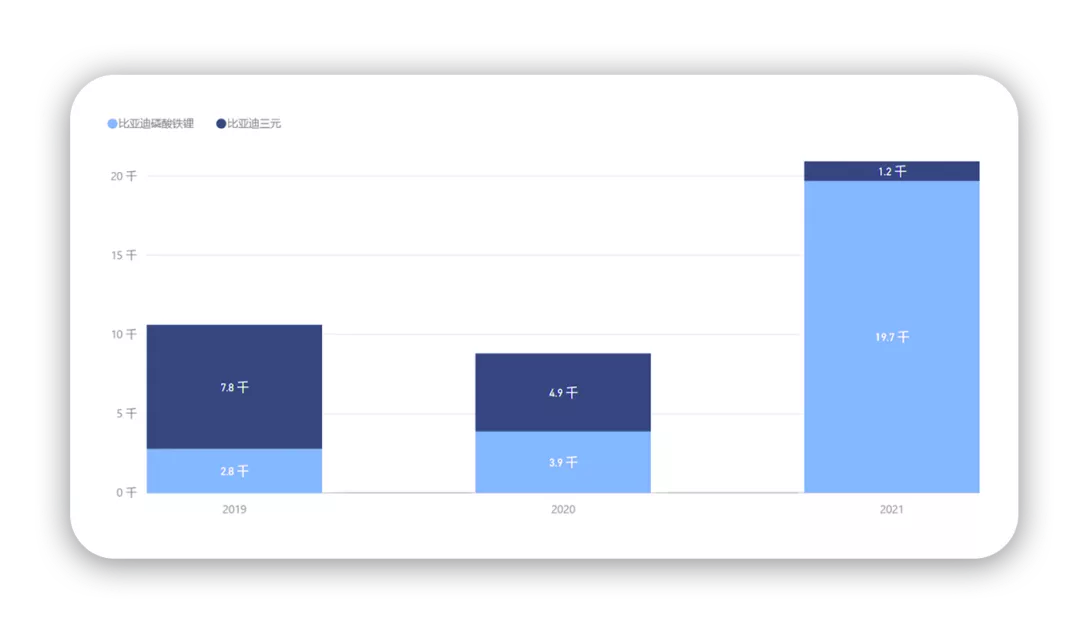

BYD’s chemical system switch

Let’s review, we can roughly see that BYD switched from iron phosphate to ternary in 2021. That is to say, in 2019 it was 7.8GWh vs 2.8GWh, in 2020 it was 4.9GWh vs 3.9GWh, and in 2021 it achieved 19.7GWh vs 1.2GWh.

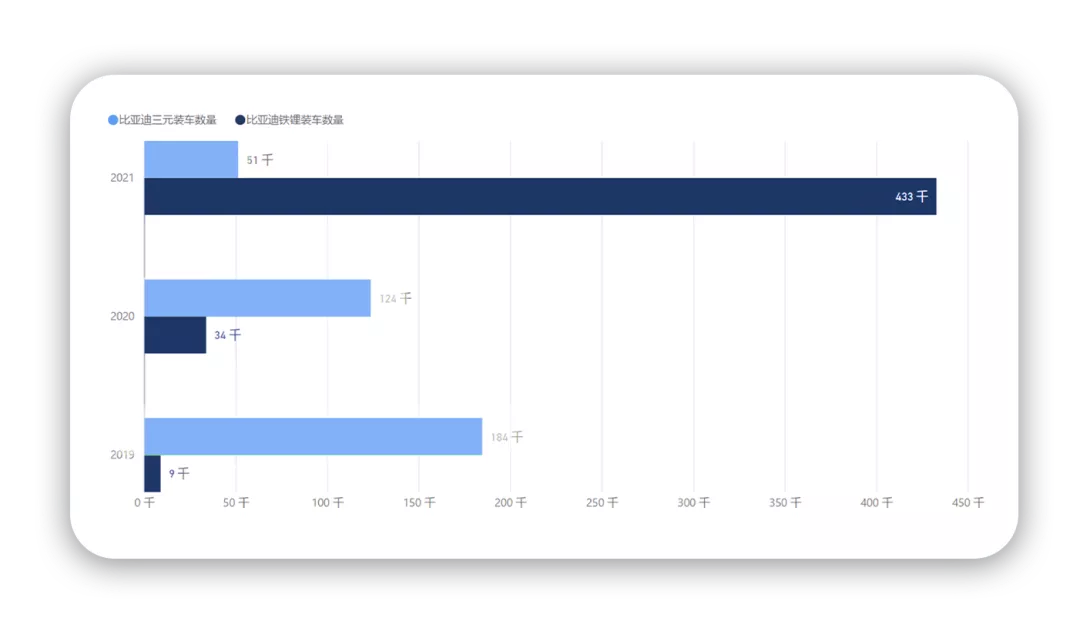

In other words, BYD’s iron phosphate switched from 9 thousand vehicles in 2019 (mainly commercial vehicles) to 34 thousand vehicles in 2020 (Hanhe commercial vehicles), to 433 thousand vehicles from January to November 2021. While the number of iron phosphate vehicles dropped from 184 thousand in 2019, to 124 thousand in 2020, to 51 thousand in 2021 (mainly in the PHEV segment) – the transition here is still very rapid.

According to the monthly trend chart in Figure 5, the switch is more obvious.

According to the monthly trend chart in Figure 5, the switch is more obvious.

BYD’s external supply situation (Fudi battery)

From the current trend, as BYD’s own usage increases, Fudi’s dependence on BYD’s own batteries is rising. Except for supplying more than 200MWh to FAW from May to July, recent shipments have been relatively low.

My view is that it is actually difficult to open up the second-line in the current pattern. The main logic is to focus on ternary materials before, but it is not easy to switch to lithium iron phosphate quickly.

Figure 6 shows the customer breakdown of Fudi batteries in 2021.

I think the core logic is that in 2021, there are still more customers choosing ternary materials among passenger car customers. In this regard, the development achievements of CATL are evident. In mid-November, CATL supplied 107MWh to ZER0-run and 235Mwh to XPeng, which is still very good.

Figure 7 shows the customer development of CATL.

The optimization of battery suppliers for new energy vehicle manufacturers is also very interesting. XPeng’s volume this year exceeded expectations. In fact, the share obtained from Ningde is limited, which is why joining CATL happened. This part of the volume effectively supported recent deliveries. From the current point of view, in the expansion of the Wuhan base in the future, CATL will occupy a relatively large share. Next year, XPeng’s volume may revolve around lithium iron phosphate, which is quite interesting for CATL’s breakthrough in the next step.

Figure 8 shows the distribution of battery suppliers for XPeng cars in 2021.

In my opinion, BYD’s identity as a complete vehicle enterprise still hinders the progress of Fudi’s external supply. Therefore, the order of opening up the situation in overseas auto companies is more important in the next step.

Summary: The power battery technology pattern in 2022 is mainly developed overseas around 4680, and domestically, development work on 4680 and various replacements of lithium iron phosphate will continue. This is just an opening statement.

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.