Editor’s Note: Recently, a well-known electric car out-of-control accident once again brought the “one-pedal” mode to the public’s attention. But do you really understand the “one-pedal” mode? How did it develop from scratch to what it looks like today?

Chris Perkins, a senior editor of the American “Road & Track” magazine, wrote the following article to tell the story of the past and present of the one-pedal mode. At the same time, from the perspective of users, he also put forward some of his own views and suggestions on this controversial technology.

If you are driving a Tesla for the first time, it is very likely that the following scene will happen: you are driving your beloved Tesla with friends for a ride, everything goes smoothly, until you encounter the road condition that needs to be slowly decelerated. At this time, you instinctively lift your foot off the accelerator pedal to step on the brake pedal. However, before stepping on the brake pedal, bang! The car has almost stopped, and at this time, friends in the back seat may question your driving skills.

In fact, this is exactly the effect of energy recovery. You can also say that this is one of the great features of electric cars. While using the motor to reduce the vehicle speed, it also recovers some energy to the battery to increase the range. Many electric cars have such a braking mode, which is the well-known one-pedal driving, allowing you to release the accelerator pedal and make the vehicle stop completely without stepping on the brake pedal.

In fact, the energy recovery mechanism did not appear for the first time on electric cars today. I think many car enthusiasts probably know Jay Leno and know that he has collected a lot of cars. Among his many collections, there is a 1916 Owen Magnetic, which is a hybrid model more than 100 years ago, and it has the function of energy recovery. The infamous EV1 introduced by General Motors used energy recovery to increase the range, and it combined mechanical braking and motor energy recovery through an extremely complex line control system using what we now call the two-pedal control. According to a report at that time, energy recovery can meet 95% of the deceleration needs of cars at low speeds.

From EV1 to modern regenerative braking, there is a clear historical timeline of the development of regenerative braking. Initially, engineer Alan Cocconi brought regenerative braking with a single-pedal logic drive system to the EV1 through a solar prototype vehicle called the Impact. After leaving the project, he brought the technology to his own company, AC Propulsion, and Tesla’s earliest powertrain solutions were from this company.

Toyota’s first-generation Prius was the vehicle that truly popularized regenerative braking to more ordinary consumers. The first-generation Prius used a two-pedal mode, which continues today. Meanwhile, most electric cars use two-pedal mode to implement regenerative braking during braking.

However, Tesla chose a different route. Starting with the Model S, all of their models produced afterwards have opted for a single-pedal mode. When the accelerator pedal is released, regenerative braking immediately kicks in; when the brake pedal is pressed, the traditional hydraulic braking circuit is activated. Dave Vanderwerp, director of vehicle testing at Hearst Autos, once suggested that Tesla adopt this method because it feels more natural when depressing the brake pedal – two-pedal mode usually makes the driver’s foot feel bouncy because there is no direct connection between the brake pedal itself and the hydraulic braking circuit. At the same time, single-pedal mode may be cheaper and easier to design.

Initially, Tesla offered drivers a range of adjustable regenerative braking options, with the low regenerative braking option mimicking traditional engine braking. In 2020, Tesla removed this option via OTA and made the use of strong regenerative braking mandatory. Under this setting, the vehicle will eventually come to a stop if your foot completely leaves the accelerator pedal.

When Tesla’s regenerative braking was still adjustable, using the one-pedal driving mode was more efficient than the low regenerative braking option. As depressing the brake pedal did not activate the motor’s regenerative braking, the vehicle, while not accelerating, either coasted or slowed down through hydraulic braking, wasting a significant amount of kinetic energy. However, when Tesla stopped providing drivers with choices, the vehicle was locked into its most efficient driving mode. Recently, Tesla also started providing a new feature where a mechanical brake is mixed in when the battery cannot accept regenerative energy so that regenerative braking now depends on many factors, from motor design to battery charge level, and even the temperature.

The regenerative braking strategy employed by Tesla is unique among electric vehicle manufacturers. While many other electric vehicles also offer one-pedal driving or an aggressive regenerative braking strategy that can bring the vehicle to a stop when the accelerator pedal is released, most vehicles can also activate regenerative braking through the brake pedal, making the one-pedal mode confusing.

The main reason for the coexistence of these two situations is that, although all electric vehicle manufacturers set up regenerative braking, not every user is willing to use one-pedal driving mode.

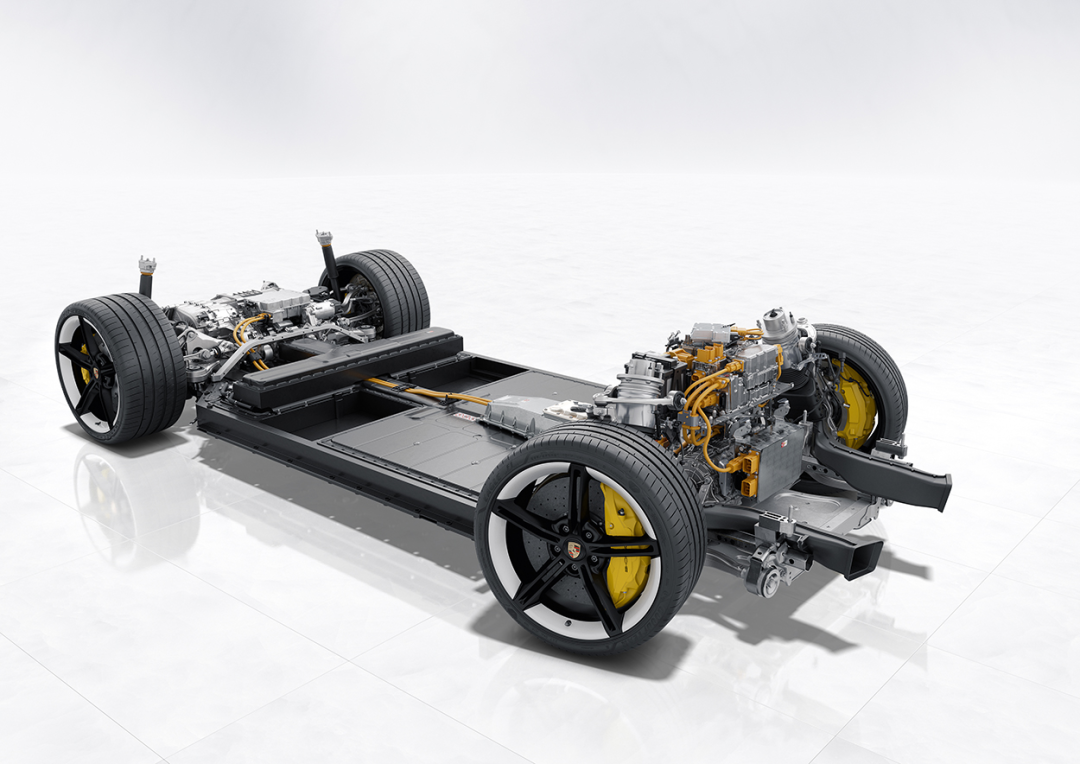

When Porsche’s first electric vehicle, the Taycan, was first unveiled, it did not offer any type of one-pedal driving mode, which drew attention. Although Porsche chose to primarily use the brake pedal to recover energy, they put visible efficiency at the forefront. The electric motor’s braking can produce up to 0.3g of deceleration, which basically covers most deceleration scenarios in daily driving. If greater braking force is required, the mechanical brakes kick in. Porsche proudly claims that it can recover up to 265kW of energy back to the battery, more than any other automaker. Furthermore, Taycan even keeps recovering energy when the ABS is triggered.

By default, the Taycan generates slight kinetic energy recovery when lifting the accelerator pedal, providing a sense similar to engine braking. Additionally, there is a button on the steering wheel that activates a stronger kinetic energy recovery program, which feels more like downshifting a high-displacement engine to second gear. Moreover, the Taycan also has an adaptive kinetic energy recovery mode that dynamically adjusts the retarding force based on actual situations through cameras and radar. For example, if you encounter a slow-moving vehicle on the highway, the Taycan will automatically activate a slight kinetic energy recovery to decelerate. Similarly, in a downhill scenario, the vehicle will adjust the kinetic energy recovery level slightly according to environmental conditions.

Porsche claims that this is the most efficient method, so there is no need for a one-pedal mode. For most people, this is also a more natural and familiar driving mode, particularly during intense driving. On the track, obtaining predictable and gradual deceleration by lifting the accelerator pedal and using the brake pedal to control more precise braking force is essential. Although the Taycan has track capabilities, it is not a race car, but this method allows you to drive the vehicle more smoothly and safely during intense cornering.

The Taycan’s approach made me wonder whether the one-pedal mode is just a gimmick when the vehicle can initiate kinetic energy recovery in other ways. What is the difference between activating the energy recovery by lifting the accelerator pedal and pressing the brake pedal from 35 mph to a complete stop?

A staff member at Polestar offered a solution in theory, stating that there is no significant difference between the two modes on a Polestar because both the single-pedal and two-pedal modes are available in the car, each providing advantages in different road conditions and allowing users to choose freely. However, on highways, the single-pedal mode is less efficient and can feel like dragging an anchor, making it difficult to maintain constant speeds, unless the cruise control is used. This is not a problem for everyone though, and the Polestar users often switch to the single-pedal mode for city driving because of its efficiency and convenience, but switch it off when driving on highways.

A staff member at Polestar offered a solution in theory, stating that there is no significant difference between the two modes on a Polestar because both the single-pedal and two-pedal modes are available in the car, each providing advantages in different road conditions and allowing users to choose freely. However, on highways, the single-pedal mode is less efficient and can feel like dragging an anchor, making it difficult to maintain constant speeds, unless the cruise control is used. This is not a problem for everyone though, and the Polestar users often switch to the single-pedal mode for city driving because of its efficiency and convenience, but switch it off when driving on highways.

BMW also offers an adaptive energy recovery program on its latest electric vehicles, i4, iX, and i7. By combining camera, sensor, and navigation data, it constantly adjusts the amount of energy recovered when lifting off the accelerator pedal. On flat highways, it hardly recovers any energy, thanks to the unique three-phase synchronous electric motor used in BMW vehicles. Unlike many other electric motors, BMW’s motor can rotate freely, improving efficiency under the circumstances. The adaptive mode works similarly to the Taycan mode in other situations, providing weaker energy recovery when going downhill and stronger recovery when a vehicle is detected in front. In addition, the vehicle can learn the users’ most frequent routes and adjust the energy recovery program to improve commuting efficiency.

Using adaptive energy recovery is the most effective way to drive a BMW electric car, but BMW still provides other settings to better suit users’ preferences. The more aggressive energy recovery has attracted not only Tesla users but also those who have driven BMW’s first electric vehicle, the i3, which has a true single-pedal driving mode. BMW has also added energy recovery settings to the brake pedal, offering around 0.2g deceleration from energy recovery before mechanical brakes are engaged.

Stephen Kosowski, Kia’s North American long-term planning manager, said that adjustable regenerative braking is a good choice. “It depends on the environment and situation,” Kosowski said. “Regenerative braking does bring many driving styles to EV drivers: some people do not like regenerative braking, while others do, and adjustable settings provide them with flexibility.” In addition, Kia has data showing that their EV users adjust the regenerative braking force by using the shift paddles behind the steering wheel. Kosowski also responded to comments from other automakers, believing that single-pedal mode may not be more efficient in stop-and-go situations, and may even be less efficient on highways.

If we have to draw a conclusion, it may be that we don’t have to be too obsessed with the single-pedal mode. It is undeniable that this is a clever function on EVs, and some people may like this new way of controlling the car. But if you don’t like it or don’t want to use it, it’s just a loss of a little extra range. “I think the best solution is to drive the vehicle in the way that everyone likes, and as for how to achieve more range gains, let those range enthusiasts worry about it.” Fortunately, except for some vehicles, most electric vehicles offer users a range of regenerative braking force options to choose from.

As for myself, I am still used to the braking method of traditional gasoline-powered cars, lifting off the throttle and stepping on the brake, after all, it is muscle memory. If my daily car becomes an electric vehicle someday, I would definitely prefer a very weak regenerative braking force, which is comfortable for passengers as well. And in my brief experience of driving electric cars a few times, using single-pedal mode has always been quite refreshing, but if you have been driving in the city for a long time, controlling the lifting range of your right foot is no different from the feeling of stepping on the clutch in the manual transmission era. And I also have to consider whether passengers are comfortable sitting, maybe I’m not that good, but sometimes I really don’t like single-pedal mode. By the way, Tesla recently pushed a new feature, that is, when the battery cannot accept the energy of regenerative braking, it will mix in a part of mechanical braking when lifting the accelerator pedal. Why do I feel like I’ve gone through a big circle and returned to the starting point?

For these new ways of operating vehicles, I still believe that automakers should fully educate, or teach users how to use them, rather than just selling cars, with the attitude of “It’s not my problem if you can’t drive it.” At the very least, more options should be given to users so that they can choose the most familiar way to control the vehicle. Think about changing people’s habits in a flash, you must be the next Steve Jobs to do it.

-END-

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.