China EV Supply Chain – observations on auto semis output, and China’s long-term opportunities

By Zhu Yulong

Yesterday, a friend of mine discussed with me their thoughts on Morgan Stanley’s “China EV Supply Chain – observations on auto semis output, and China’s long-term opportunities”. The chip shortage in 2022 has presented a new form:

-

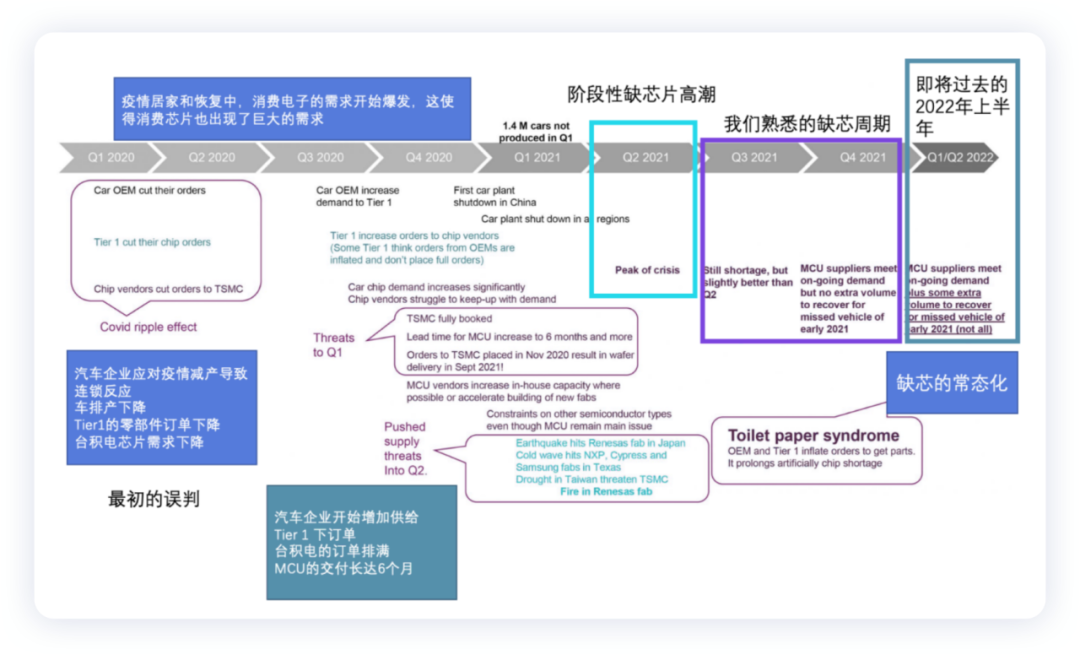

Since last year, most Tier1 suppliers have followed the automakers’ priority of ensuring supply and have placed more orders (actual demand is 100%, orders given are 120-130%). After the actual chip manufacturers distributed the chips depending on the needs of different Tier1 suppliers and automakers, only 90% of the chips were received. This means that after all the fuss, automakers have no ability to build a buffer to stockpile chips.

-

Looking at domestic and foreign automobiles, the product planning cycle is typically 5-8 years. Originally, the strategy was to build strategic inventory through a large number of orders, so as to increase reserves in case of demand. However, this has objectively increased the difficulty of adjusting the goods. Since there are no chips in stock, forecasting becomes very difficult and this has objectively led to exhaustion in the first half of 2022. The supply battle of 2021 has consumed a lot of funding and resources, and a new strategy is needed in the market in 2022.

-

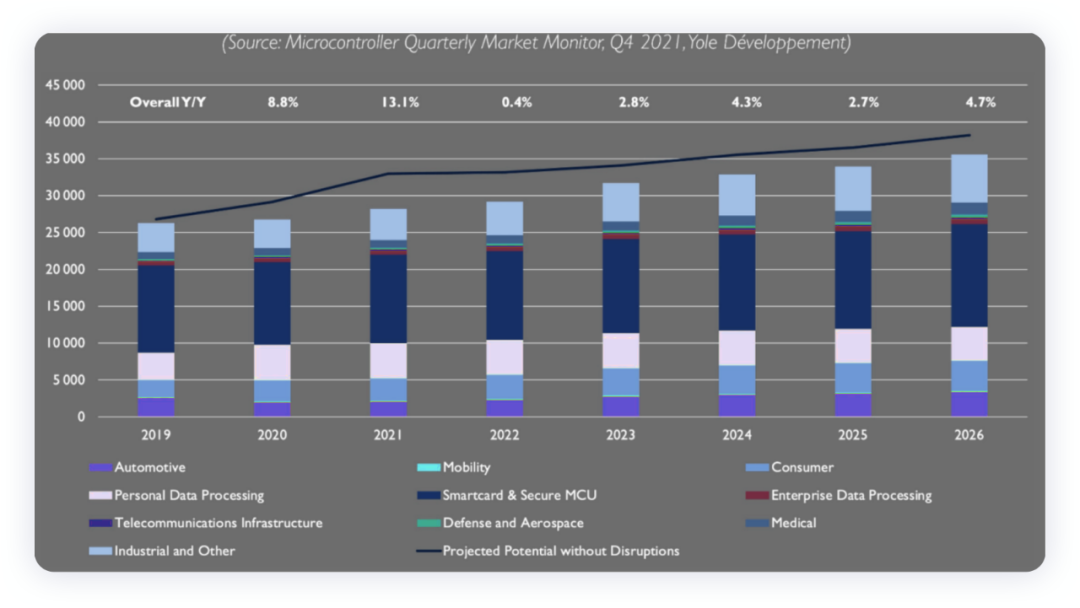

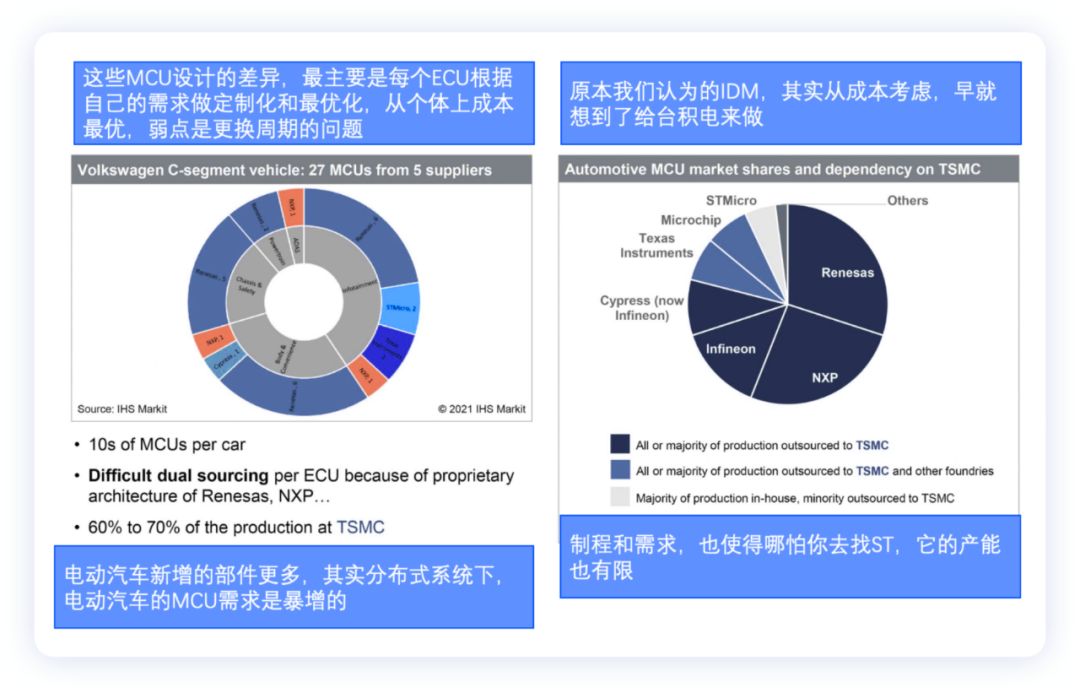

Looking at the supply bottleneck of MCUs and dedicated ASICs, the stable cycle of car-mounted MCUs has led to MCU prices declining very slowly over the past several decades. However, in 2021, the price even exceeded the Tier1 suppliers’ expectations, and the limited investment in mature processes by manufacturing companies means that the price is expected to continue rising for the next five years. This seriously undermines the bargaining power and actual profits of Tier1 suppliers.

Therefore, as I see it, 2022 has actually entered a state of normalized chip shortage. In Europe and the U.S., due to the continuous chip shortage, both new and used car prices have risen, and automakers do not have the sustained motivation to pay high prices for chips. In China, the emergency adjustment of chips and engineering in 2021 has caused many after-sales problems. Continuing this strategy in 2022 requires greater determination (rising costs and declining quality). According to my friend, we are constantly discussing either the chip shortage or quality problems brought about by previous changes. This has become a normalized shortage, and the entire supply chain is beginning to optimize itself, creating popular products for niche markets and focusing on supplying high-profit models.

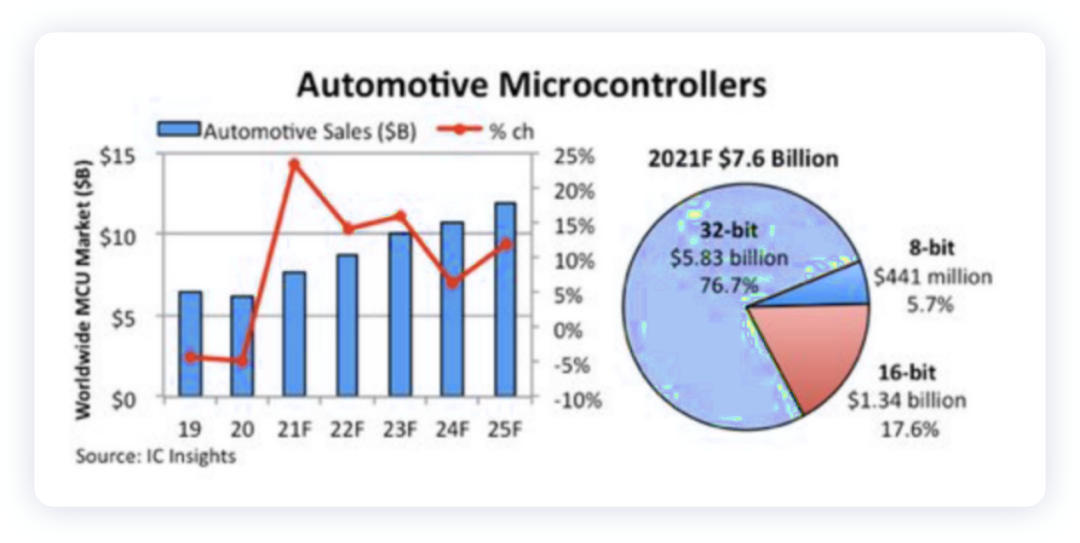

The value distribution of MCUs is shown in the graph below, with 32-bit MCUs accounting for 76.7%, 16-bit MCUs for 17.6%, and 8-bit MCUs for only 4.7%. The six major mainstream MCU vendors in the global automotive market, namely Renesas, Infineon, NXP, ST, TI, and Microchip, account for over 90% of the market share for automotive MCUs.

-

8-bit MCUs (Microchip, Infineon, NXP) are used for controlling low-end applications such as fans, air conditioning panels, wipers, sunroofs, windows, seats, and doors.

-

16-bit MCUs are mainly used in traditional power modules and have no new applications.

-

32-bit MCUs are divided into high-function safety and multi-function varieties (Renesas, Infineon, NXP, and ST), covering powertrains (both traditional and electric), chassis electronics (such as ESP and EPS), cabins (instrument clusters and center consoles), body controls, ADAS sensors and controls, parking functions, and more.

Tesla has used many low-power Bluetooth products of TI’s MCU series, and we will compare them by product category later.

The evolution of the Automotive Semiconductor Shortage

Throughout the process, the major problem is that general-purpose MCUs and automotive MCUs are concentrated in the hands of the six largest automotive semiconductor companies, and each automaker has provided its preferred MCU supplier list according to their own requirements. Despite the originally smooth supply curve, everyone has a cache surplus. In the first half of 2022, only a few companies can afford enough chips at reasonable prices.

Note: This is similar to batteries. How many batteries is suitable to buy when the price increases by 40% and how many are sufficient?

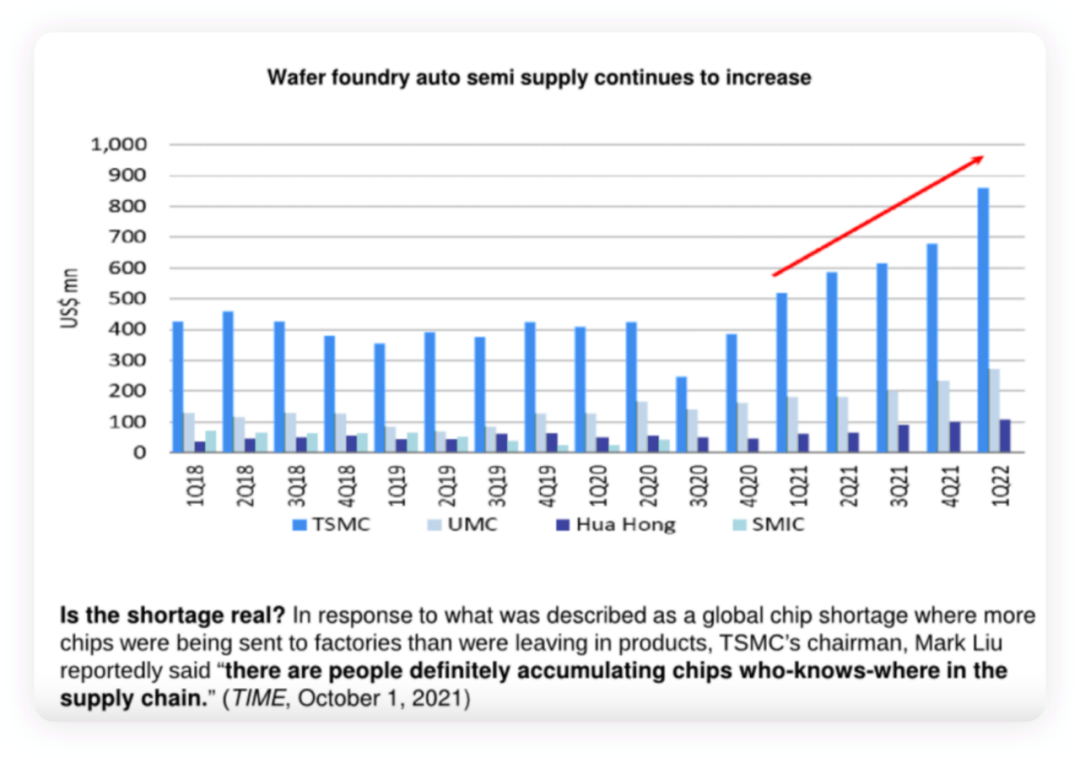

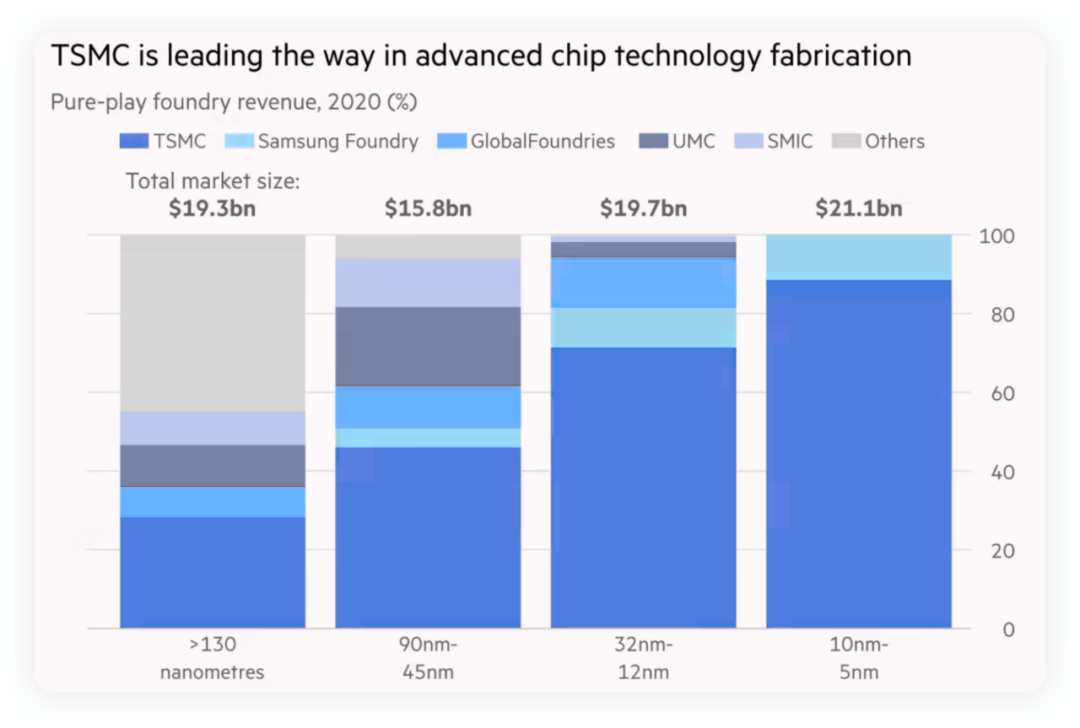

In the first quarter of 2022, TSMC’s financial report shows that revenue reached a historical record of about $17 billion, a year-on-year increase of 35.5%; net profit was about $7 billion, a year-on-year increase of 45.1%. From a technical standpoint, revenue from advanced processes with 16nm or less accounted for 64% in 2022Q1. Among these, 5nm contributed 20% of revenue, 7nm contributed 30%, 16nm contributed 14%, and 28nm contributed 11%. The remaining processes accounted for 25%. TSMC plans to begin producing 3nm chips (N3) in the second half of 2022 and aims to produce 2nm chips by 2025.So the biggest question here is, during the period from 2021 to Q1 2022, how much has the increase in the supply of automotive MCUs and other supporting automotive chips really helped to alleviate the situation?

Does it really work?

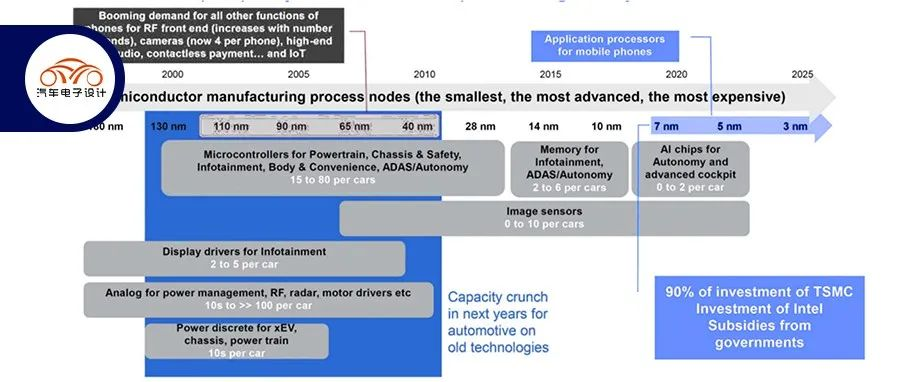

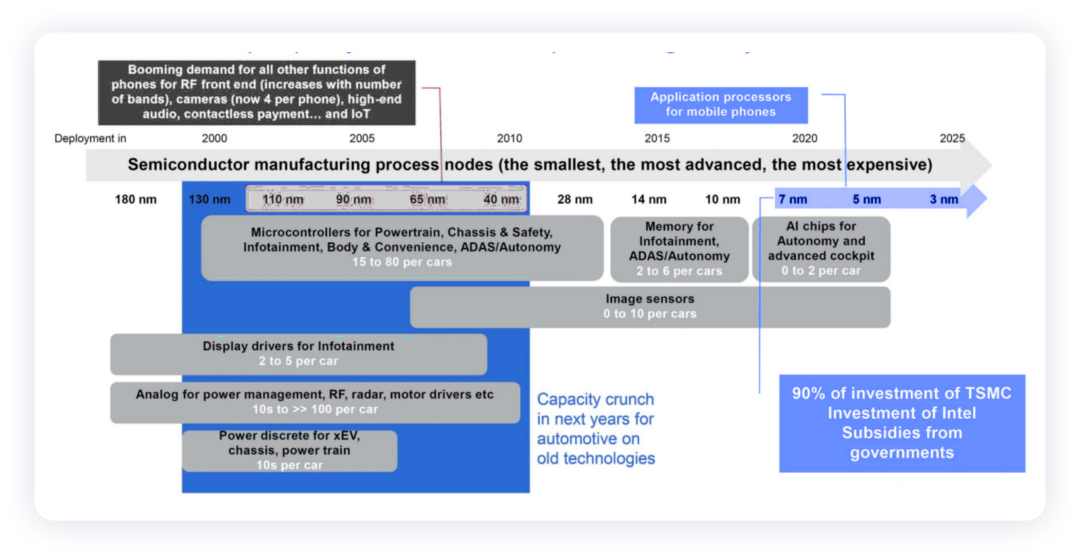

For automotive MCUs, due to cost and performance considerations, the process nodes are relatively backward, mainly concentrated in the traditional process nodes of 40nm and 56nm. In the past few years, TSMC and other companies have not made new investments. TSMC gradually increased its investment in 2021, which still resulted in a tight production capacity. The following figure shows this clearly. TSMC’s main focus is actually to widen the gap with chip foundries. Investing in more mature processes is not a very favorable decision for TSMC.

Because the production of automotive wafers still needs to pass TS 16949 certification, and with the overall demand increasing, the easing in the second half of 2022 is gradual. By 2022, even the supply of MCU semiconductor equipment is problematic, so how can the capacity expansion process go smoothly?

In electric vehicles, due to the addition of components such as BMS (CMU), PDU, DCDC, OBC, PTC, electric compressors, inverters, and VCU, if the design is complex, it is equivalent to suddenly adding more than 10 MCUs. We can compare the use of MCUs in MEB with traditional cars. Before the use of a centralized architecture, the reliance on MCUs in electric vehicles was high.

The increase in functionality, if not centralized through software, objectively resulted in a very tight MCU supply at a penetration rate of only 10%.

Summary: I believe that the automotive chip crisis, which has lasted for nearly two years, is actually continuing in another form. However, we have no way to deal with it like fighting a fire. No matter how we salvage it, our ability is limited. It’s just that when we say it out, everyone is not so excited anymore. It’s for your reference.

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.