Special Contributor | Enjoyment

Editor | Qiu Kaijun

On October 24th, after enduring a difficult 20-day period, Tesla China finally announced its latest pricing adjustment plan: the entry-level Model 3 reduced by 14,000 yuan, with a starting price of 265,900 yuan; the entry-level Model Y reduced by 28,000 yuan, with a starting price of 288,900 yuan. This price is almost the second highest price of Model 3 and Y in the past two years.

At the same time, Tesla has restarted the long-suspended “Referral Program,” hoping to continue increasing its customer base through the “old for new” approach.

Tesla often adjusts its prices, but this time it’s different. The reasons and environments for the adjustments are different, and Tesla may have reached its most difficult moment in China.

Something different about this price drop

Tesla has always been called a “good-faith enterprise” by its fans and has always priced according to its costs. Once the cost of the supply chain falls, corresponding price adjustments will be made. However, this time it’s a bit different. Recently, there has been no significant change in upstream costs, and the cost of the main material for the power batteries, lithium carbonate, has not only not decreased but has also risen to over 55,000 yuan per ton.

So why did Tesla lower its prices this time?

The main reason is that Tesla China’s order backlog is not enough at the moment. According to data estimated by TROY, a well-known Tesla order tracker overseas, Tesla China’s order backlog was 14,200 in September and fell to 10,800 in October.

In other words, if the insurance subsidy policy continues, Tesla’s Shanghai factory will no longer be able to sustain its orders in China. Even if the Shanghai factory’s output in October mainly serves exports, the domestic orders can be depleted within a month. Therefore, the Shanghai factory has adjusted its production pace moderately to cope with the declining demand.

This is Tesla’s first sudden price cut due to decreasing demand, rather than cost reduction.

How to overcome the innovation chasm

Jeffrey Moore, an American writer, once wrote a book called “Crossing the Chasm”, which describes the biggest obstacle that high-tech products will encounter in the marketing process: there is a huge “chasm” between the early market of high-tech enterprises and the mainstream market. Whether the high-tech product can successfully cross the chasm and enter the mainstream market, and win the support of practical users, determines its success or failure.

The author created the “Technology Adoption Lifecycle” model, which divides consumers into five categories: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards; and divides the market into early market, mainstream market and laggard market.

Early markets are mainly composed of innovators and early adopters, dominated by early adopters who are essentially “early users who love to try new things.” Early adopters provide most of the orders for companies during this stage, while the mainstream market consists of early and late majorities, who make up two-thirds of the entire consumer base and represent the main source of significant revenue for companies. They are also the customer base that companies must strive to win over and the largest customer base required for companies to continue to develop sustainably.

Early markets are mainly composed of innovators and early adopters, dominated by early adopters who are essentially “early users who love to try new things.” Early adopters provide most of the orders for companies during this stage, while the mainstream market consists of early and late majorities, who make up two-thirds of the entire consumer base and represent the main source of significant revenue for companies. They are also the customer base that companies must strive to win over and the largest customer base required for companies to continue to develop sustainably.

However, early adopters and early majorities have different demands, and are separate submarkets with a deep and wide chasm referred to as the “gap.” If companies cannot bridge this gap, it means they cannot enter the mainstream market and they may likely fail.

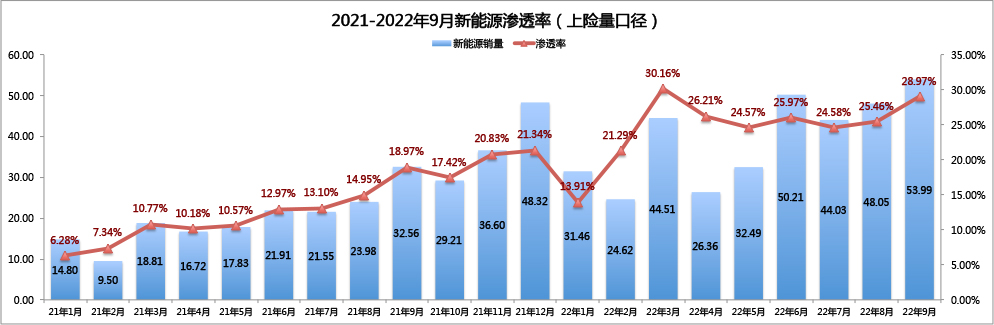

After reading about this innovation model, let’s now take a look at the penetration rate of China’s new energy passenger car market.

In 2021, China’s new energy market penetration rate was 13.84%. In 2022, the penetration rate of China’s new energy market during the first nine months reached 24.20%.

And such a performance in market penetration is exactly in between the early adopters and early majorities described by Moore, and is the “gap” that needs to be bridged.

According to Moore, the essential reason why this gap exists is that early adopters and early majorities have completely different purchasing logics (essentially, they are two completely different target customers).

Early adopters always pay attention to the technological trends in the industry, partly because of their interest in technology, and partly because they can see the long-term value of disruptive products. At the same time, early adopters are often willing to tolerate some minor flaws in disruptive products, because for any disruptive product that has just been introduced to the market, small defects are inevitable. This description is almost identical to the delivery quality and customer feedback of Tesla Model 3 and Y during 2019-2020.

Early adopters always pay attention to the technological trends in the industry, partly because of their interest in technology, and partly because they can see the long-term value of disruptive products. At the same time, early adopters are often willing to tolerate some minor flaws in disruptive products, because for any disruptive product that has just been introduced to the market, small defects are inevitable. This description is almost identical to the delivery quality and customer feedback of Tesla Model 3 and Y during 2019-2020.

But early mainstream consumers are completely different. They are very cautious and want to see the progress of disruptive technology, but they are not willing to personally test and troubleshoot the problems that may arise in these products time and time again. Once they decide to use a certain product, early mainstream consumers hope that it can not only operate normally, but also integrate closely with their existing technological foundation.

Early mainstream consumers also have a characteristic that they want to see reasonable competition. With competition, they can not only buy products at lower prices but also quickly find alternative solutions once problems arise. Most importantly, through competition, early mainstream consumers can ensure that they buy products that play a dominant role in the market. This is why recent disputes between Tesla and its customers in the past two years (such as price reduction and rights protection, etc.) are such an important reason.

Today, Tesla in China is facing such a gap. On the one hand, the competition of independent brands is becoming more and more fierce, and there are more and more products that can be compared with Tesla. On the other hand, the mainstream customer group that Tesla faces is undergoing drastic changes-they hope for more space, better interior, more comfortable tuning, and a smarter cockpit that is more in line with the Chinese market. And Tesla cannot provide all of this at the moment.

And what about FSD that Tesla can provide? Currently, it cannot be fully experienced in China.

Adding 3cm to the length of the rear seat cushions? The customer’s perception is limited.

Replacing the 72-degree battery pack? This means that the price will rise again.## Translation

Replace with a brand-new interior (the one on the new Model S)? For most customers, “a newly whitewashed bare room is still a bare room.”

Keep in mind that the Model 3 has been on the market for 6 years. By the standards of China’s new forces, at least a new generation should have been released by now.

Can Tesla “Bridge the Gap”?

1. Tesla’s dealership network is too concentrated in first- and second-tier cities

Let’s start with the numbers. As of September 30, Tesla has a total of 242 stores in China, an increase of 16 stores from 2021. However, in the first half of this year, Tesla also closed 19 stores (a net increase of 16 stores). This shows that Tesla is continuously adjusting its store size.

Moving on to the layout, first-tier cities account for the highest proportion at 45%, second-tier cities at 35%, third-tier cities at 19%, fourth-tier cities at 1%, and fifth-tier cities have no layout. This is the latest structure after this round of adjustments. Tesla has increased the number of its stores in second-tier cities and closed some poorly performing stores in fourth-tier cities. This means that 80% of Tesla’s stores are in first- and second-tier cities.

Meanwhile, the sales structure from January to June of this year shows that Tesla’s sales in first- and second-tier cities accounted for as much as 93%. This means that the 20% of stores in cities at third-tier or below contributed only 7% of sales, roughly equivalent to monthly sales of around 40 vehicles per store.

The inefficiency of Tesla’s expansion into lower-tier cities contrasts sharply with the monthly sales of 150+ vehicles per store in first-tier cities.In terms of urban layout, the distribution of sales networks is excessively concentrated in first and second-tier cities, leading to further concentration of sales in these cities. This is the urban layout gap that Tesla needs to overcome.

Compared with BBA, Tesla still needs a significant increase in market share in third-tier and lower markets.

According to the latest insurance coverage data from January to September, the penetration rate in all first-tier cities (except Beijing) has exceeded 30%, and the insurance coverage data in the top 15 second-tier cities is also approaching 30%.

Competition in the new energy vehicle market in first and second-tier cities is no longer the main focus of the next stage. In the future, the new energy vehicle growth focus in the Chinese market will be in third-tier and lower cities and in the price range of ¥100,000 to ¥2,000,000, which is the product gap that Tesla needs to overcome.

2. ¥100,000 to ¥2,000,000 is the main incremental space for future new energy

First, let’s look at the sales data broken down by price range from January to September.

It can be seen that in the Chinese market, the sales proportion of passenger cars priced between 100,000 yuan and 2 million yuan is 49.55%, while the sales proportion of those priced between 250,000 yuan and 500,000 yuan is 19.68%.

In the price range of 100,000 yuan to 2 million yuan, the penetration rate of pure electric vehicles (EVs) is 12.99%; and in the 250,000 yuan to 500,000 yuan range, the penetration rate of pure EVs has reached 20.89%, which is also the price range of Tesla’s mainstream models.

It can be seen that in China’s market, passenger cars priced between 100,000 yuan and 2 million yuan have the largest sales proportion, but the penetration rate of pure EVs is low, and Tesla’s product lineup in this price range is still incomplete.

In the future, new energy vehicles priced between 100,000 yuan and 250,000 yuan will become the main growth area.

When a company’s product does not meet the mainstream and fastest growing market demand, it will naturally encounter its own ceiling.

Of course, many people may say, “Tesla doesn’t need to go to this price range, they can just grab market share from BBA!”

That’s true, but once Tesla chooses this strategy, it needs to accept: the annual sales ceiling of any single brand of BBA in China is about 700,000 to 800,000 vehicles (including imported cars). If we deduct some of BBA’s entry-level models, this number will be even lower, at around 600,000 to 700,000.

This means that if Tesla does not have a new model priced below 200,000 yuan in the future, even with locally produced Model S or Model X, the ceiling for Tesla’s annual sales in 2023 will be only 700,000 vehicles!

Conclusion

Tesla’s this price adjustment is not a conventional “cost-driven” one but a practical “competition-forced” one.On one hand, Tesla’s order backlog is rapidly declining due to the aging of its products and the intense market competition. Even after the launch of its more than 14,000 yuan discount policy, as of the 27th, it was reported that the newly added orders for Tesla’s lowered prices were about 30,000, which is slightly lower than expected overall performance.

On the other hand, Tesla’s direct sales model and dealership network layout, which are too concentrated in first- and second-tier cities, will also cause Tesla to lose the rapidly growing new energy sales in third- and fourth-tier cities and beyond.

Based on the above points, it can be concluded that without introducing new products, Tesla’s sales ceiling in China’s market will be around 700,000 vehicles by 2023.

So, can Tesla “bridge the gap” and enter the broader public market? Will Tesla “lose its charm”? Let Tesla’s sales and the market answer those questions.

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.