Author: Mr.Yu

Recently, the topic of privacy risks caused by in-vehicle cameras has once again entered the public’s view due to a certain event.

In the article “Where is Your Privacy When Surrounded by In-Vehicle Cameras?“, we discussed the logic behind the event and the privacy anxiety of users.

Before jumping to the conclusion of whether vehicles need to be equipped with visual sensors such as cameras, let’s first take a look at the policy-level requirements of DMS systems for commercial vehicles such as “two passengers and one danger” in China. And the requirements for passenger vehicles are also being formulated.

On the other side of the earth, Euro NCAP has made it clear that vision-based driver monitoring functionality will become a necessary condition for new cars to receive a five-star rating. Meanwhile, the EU has enacted regulations that, after July 2022, all vehicles with L2 and above autonomous driving systems (including passenger and cargo vehicles) must be equipped with fatigue and distraction warning systems (DDAW). After July 2024, all new vehicles will be required to install this feature.

Like it or not, the installation of cameras in the car cabin is already a trend.

It’s easy to curse along with everyone else, but listening to the industry’s voice and understanding the reasons behind it is what we should do.

A few days ago, I had a conversation with Yang Yihong, the general manager of MINIEYE’s intelligent cabin business unit, about a series of issues surrounding in-vehicle DMS/OMS cameras out of curiosity.

After this conversation, I realized that the door to installing cameras on the vehicle is far more complicated than everyone thought.

The following is a transcript of the conversation (G for GeekCar, Y for Yang Yihong):

G: From MINIEYE’s perspective as an industry player, what is the current status of the world’s major automobile powers in promoting DMS functionality?

Y: All along, people’s perception of us has been as a company that provides intelligent driving solutions. The reason we decided to enter the cabin field is because we keenly sensed the market demand and saw that the EU was beginning to formulate some related regulations.

In 2013, the EU enacted legislation related to the installation of AEB (automatic emergency braking system) and LDW (lane departure warning) for newly produced heavy commercial vehicles. The progress of domestic follow-up will probably see related mandatory standards in about 3 to 5 years.DMS and OMS are no exception, especially with the rising pursuit of technology. We believe that the time for similar policies to be introduced and implemented in China will be shortened. Starting this year, the EU mandates that all new car models with L2 or higher automation must be equipped with DMS. Therefore, we believe that the country will also introduce policy standards for the passenger car sector. We forecast that related policies will be implemented around 2024 to 2026.

Apart from DMS, the EU will also introduce testing standards for Child Presence Detection (CPD) in vehicles, possibly as early as next year. Both the EU’s mandatory requirements and Euro NCAP’s new car ratings will be established as industry standards. Similarly, we anticipate that relevant laws and regulations will also be introduced in China.

G: So, is the competition in China not only driven by policy factors?

Y: Yes, I think one interesting thing about the cabin is that it is different from autonomous driving. Regarding autonomous driving, industry standards and laws and regulations have a significant driving effect on the entire market. People have a requirement for new functions that are driven by regulations or industry rules.

The current market situation of cabins over the years has resulted in an ever-increasing amount of in-group rivalry. In recent years, new brands and players have emerged, and the definition, tone, personalization, and consumer groups targeted by these brands are often reflected in the cabin’s functionality to provide a sense of technology or enhance the experience.

Therefore, after new brands and players enter the industry, they bring colorful and high-tech cabins. This also prompts some decision-makers of traditional brands to believe that “if new players have something, we as traditional brands must also have it.”

Therefore, the cabin market is moving faster and more aggressively than initially planned. It can’t be said that it is entirely due to industry standards but rather a positive result of competition among everyone.

G: Regardless of DMS or OMS, what technological path are the industry players in visual perception taking? What path has MINIEYE taken?

Y: The two main categories of vision-related players are 3D and 2D.

3D players mainly include sensors such as structured light and ToF.

For those who follow the 2D technological path, including us, visual perception combined with deep learning is the primary technological path we follow.Another camp is the radar camp, namely millimeter-wave radar. As we can see from some car models on the market, millimeter-wave radar is used to perform some in-cabin live monitoring.

Actually, each technology has its own pros and cons. For us, MINIEYE focuses on implementation. For car manufacturers, they certainly hope to achieve the cost-effectiveness and more application scenarios when adding any sensor. Looking at the existing four major sensor categories, 2D cameras have better advantages in extensibility and universality.

Specifically, it depends on the application. 2D cameras can achieve simple FACE ID operations like car login, while 3D cameras are needed for payment-level FACE ID and functions like face unlocking.

The technology path of millimeter-wave radar is similar. Millimeter-wave radar judges live monitoring based on the chest’s undulation. Besides, millimeter-wave radar can only determine that there is a live organism in the cabin, but it is impossible to determine whether the organism is an adult, a child or a pet. This indicates that such technologies as millimeter-wave radar are relatively single in terms of scenarios.

As mentioned earlier, CPD child detection is a relatively challenging type of implementation. Future regulations will undoubtedly require differentiation between adults and children in in-cabin detection.

Therefore, all things considered, we believe that the 2D camera path is more functional in comparison.

G: From the perspective of MINIEYE as a player in the industry, what is the current status of the world’s major automobile powers in terms of policy or standards in promoting DMS functions in cars?

Y: We have actually done a lot of interactive functions, such as various body language interactions. This is not imagination, but we have indeed received real needs from customers.

The viral spread of short video content mentioned earlier has spawned many novel ways of interaction.

Not only inside the cabin but also outside, we have received some needs for cars to respond in cooler ways. For example, standing outside the car to perform some external interaction, hoping that the car can cooperate with me by dancing, flashing lights, or opening the window.

This is the demand based on the marketing and promotion activities that brands carry out on short video platforms, hoping that their own products look cooler, and everyone will find it interesting, right?

Personally, for the cabin level, safety and comfort are the true hard needs and are the most valued by the industry. But for now, many needs are still soft demands at the promotion and dissemination level when it comes to DMS.

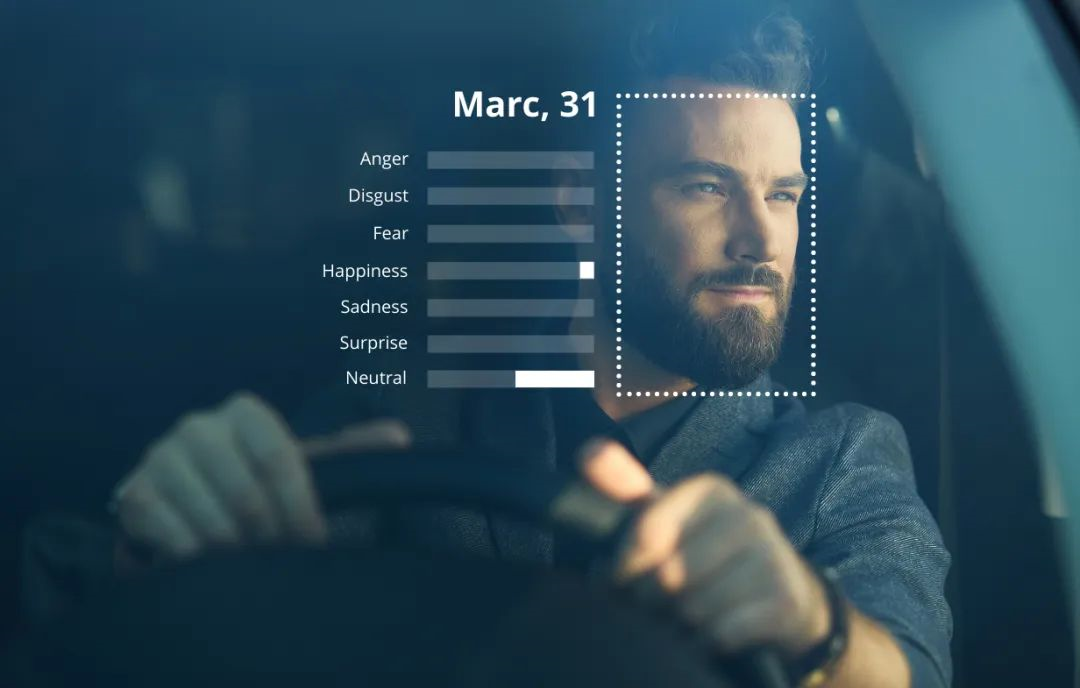

G: Let’s expand and talk more about hard needs. If we look at DMS and OMS together and the functions they can achieve, such as driver identification, fatigue monitoring, and live detection that everyone knows, what are the actual application scenarios?Y: The most solid hard requirement is DMS (Driver Monitoring System) that monitors the driver. However, the DMS here is not the traditional concept of fatigue, or those things that come to mind for aftermarket and commercial vehicle scenarios. I think fatigue and distraction are both judgments of attention.

Why do we emphasize judgment of attention? Now, whether it’s L2 or various sayings of higher levels of L2, as intelligent driving becomes increasingly popular, everyone’s trust in related technologies is different. As we can all see, in recent years, some tragedies caused by excessive trust in autonomous driving technology have been constantly appearing. Undeniably, there are still many scenarios that automatic driving needs to continuously improve itself in.

The requirements for the driver’s attention in taking over the vehicle will actually be the core task of DMS technology in the next few years.

For the system, it is very important to judge whether the driver is suitable for taking over now, and whether the corresponding auxiliary driving status should be continued. This involves a lot of very meticulous work, including analyses of the driver’s gaze, current body state, and facial micro-expressions. These cannot be simply summarized by using the states of “fatigue” or “distraction”.

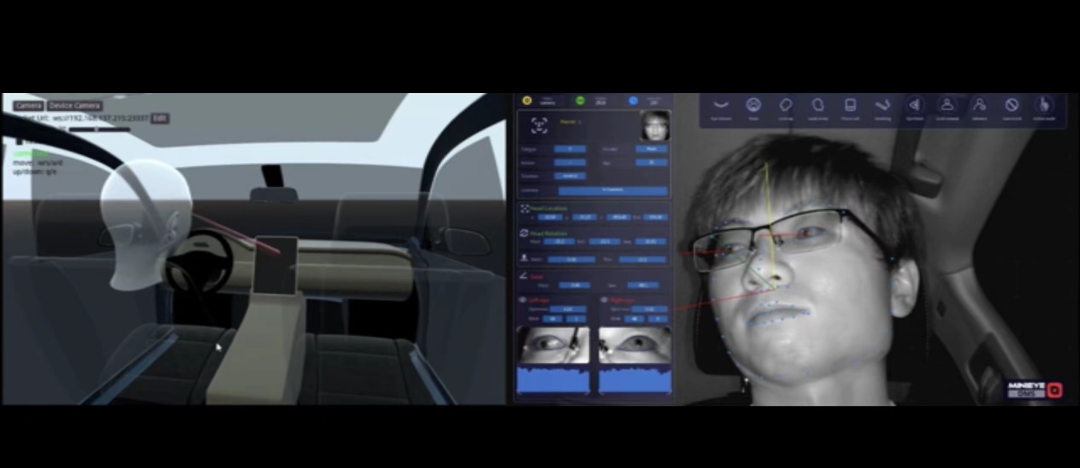

In 2021, when we announced the I-CS (In-Cabin Sensing) mass production plan, we proposed the five major scenarios of seamless access, safe takeover, fatigue monitoring, child care, and multi-person entertainment. For the physiological discrimination standards of safety supervision, we referred to clinical human reaction data for diagnosis and summary.

This is also the biggest challenge for us in the EU export project and the part where MINIEYE thinks it is best at. We hope to seriously judge a person’s true physiological status from his clinical performance instead of using standardized fixed actions as targets.

G: Actually, in a narrow sense, will the expression of the function be that everyone may be trying some teasing actions towards the in-car camera, and then seeing if the system’s reaction is the expected one, to judge whether the technological product is good or not? What is the difference between the mechanism of these types of products and what everyone imagines?

Y: There is a big difference. The actions you mentioned, just now, are called Trigger Behaviors, which refer to those actions that can stimulate algorithms to respond. Imagine if the entire mechanism of DMS revolves around such a series of trigger behaviors to design and establish the entire warning mechanism, what effect would it have? The system will be overly sensitive, constantly giving false alarms or even more excessive.When experiencing a mass-produced car model, we constantly receive feedback from developers who think they are driving normally but receive distracting alerts from the system. This is actually caused by over-sensitivity, which significantly affects the driving experience.

When delivering to customers, we are required to provide three different modes, including the “demo mode,” which amplifies this sensitivity. For example, when 4S stores want to demonstrate this feature, they must rely heavily on trigger behavior to detect actions such as closing eyes or turning heads, and the system will remind the driver.

In fact, these can all be achieved based on algorithms, but it won’t work for everyday driving. Actual requirements demand algorithms to reduce sensitivity to an extremely low level and only make the most extreme judgments to enhance the ultimate driving experience.

But I think reducing the sensitivity is only a temporary solution. The most crucial aspect is for the people who develop machine learning algorithms to not treat fatigue or distraction as a computer vision task. We indeed need to understand why people get tired and what physiological responses occur when they do.

Therefore, in our opinion, many cabin-related functions are interdisciplinary products. If you only understand technology, care only about your own algorithms, and only care about the results of the images, you won’t be able to implement DMS functions successfully.

G: Actually, there are still some corner cases. In our smart cabin evaluation work, we have encountered some strange bugs in the past. For example, in a car with DMS and OMS monitoring, I might instinctively put my hand on my chin or my mouth when thinking. The camera captures that and says there is someone smoking in the car, and then it forces ventilation by opening the window. This kind of obvious miscategorization is not uncommon. What could be the general reason behind this?

Y: From a macro perspective, false alarms can be summarized into two categories.

One category can be summarized as the natural defects of CV (computer vision). No matter how much optimization is done, no matter how much data is collected, it cannot be completely avoided and can only achieve the best results through continuous optimization.

For example, when monitoring fatigue or smoking, sometimes we receive corner cases of system false alarms. With just the collected images, it is sometimes difficult even for the human eye to accurately judge if someone is fatigued or has closed eyes, if someone is smoking, or if someone is holding a pen. In driving scenarios, sometimes it is even difficult for human eyes to make accurate judgments. Think about it: the human brain is so much more complex than the neural networks being used today. Therefore, this category of problem can be explained as a natural defect of computer vision.

The other category is very refined and specific, and is highly related to whether the supplier has thoroughly researched a particular function.# Translation in English

Let’s take smoking as an example. Some solution providers may not perform entire face recognition but choose to crop a small area of the image as an icon. This may be a small part of pixels (100×100, 100×200) near the mouth, which will affect the final false detection rate in multiple ways, including cropping size and annotation. This requires solution providers to try repeatedly and even invest boldly in advance. For example, on the cropping size, whether to learn specific objects, specific gestures, or both together. There will be many different versions of these details.

Solution providers like MINIEYE will definitely deliver the best version to customers. This is also one of the biggest advantages of MINIEYE mentioned at the last year’s conference, that even on a single function, multiple different solution versions or algorithm versions will exist.

G: I understand that computer algorithms still cannot rely on general knowledge to understand the human world. So how do we balance the sensitivity of monitoring and recognition? Excessive sensitivity often causes trouble rather than convenience.

Y: It must be deduced from the experience.

When we were exporting models to Europe this year, we found that the EU’s rating for DMS fatigue monitoring is based on clinical theory. We can understand it as finding some people who do not understand the DMS technology and tiring them out for real. Then, the monitoring system’s judgment results are compared with the subject’s subjective judgment of fatigue.

This set of practices is something we have been advocating all along. There are a large number of true algorithm version test works in our process, including cooperation with many driving schools. Under the premise of ensuring safety, there will be a large amount of long-term driving data generated from the instructor’s car, and the tester must not be a developer. Because developers are too aware, even unconsciously, they will trigger some actions. The authenticity of such test results needs to be discounted.

Therefore, for us, obtaining real fatigue data from these non-R&D teams has helped our developers design very accurate thresholds. Of course, the product will only alarm when necessary, and the user experience is the best.

G: Earlier, we also mentioned that the business in the commercial vehicle industry has been in operation for some time. We have known before that the DMS will be more widely used in large commercial vehicles such as freight logistics, and the speed of popularity will be faster than that of passenger vehicles. Is the actual industry situation like this?Y: Yes. Because the biggest demand for commercial vehicles is that the buyers have a real need for regulation fatigue. This is because the object of regulation is the employees of the company, not the owner of the passenger car. If there is fatigue driving, whether it is the employee’s personal safety or property, it will be accompanied by huge risks. Therefore, companies often have stronger demands to use in-car cameras and DMS technology to achieve regulatory work.

However, for passenger vehicles, consumers themselves currently do not have very clear proactive requirements for self-management of fatigue driving. Whether it’s a car manufacturer’s customer or ourselves as a supplier, we all need to face a logic that needs to be reversed, which is that there is no strict subjective supervision requirement on passenger cars.

For the confidence of car owners, we also tend to recommend this technology to everyone in a more gentle way, such as playing music or calling important contacts, bringing some relatively gentle “stimulus” through communication. Only by assisting the DMS function in this way can there be a better user experience.

No matter how good the technology is, it needs to be packaged more in line with users’ psychology to enter the “easy to use” category.

G: Recently, there has been a conflict between the design of in-car cameras and users’ concerns about personal privacy. In recent years, with the protection of data security at the national level and the awakening of the general public’s demands for data privacy, car companies and suppliers have also been required. How do we see such issues?

Y: First of all, fundamentally, the monitoring function in the car must be offline in the design at the bottom level. Anything collected is processed locally and deleted after processing. This is a mechanism that does not store photos or videos, and is actually designed at the system level. In fact, many familiar passenger car companies are designed and required in this way. As a supplier, even if we do some OTA upgrades, the pictures and data collected on the car cannot be taken away, and they will not be stored locally.

People’s anxiety is easy to understand. A camera that appears in their field of vision can cause some concerns for consumers. In fact, from the system design level, there is no such risk in itself, but the network security defense of the entire system itself still needs to be done well.

In addition, at the social level, I think that data security and personal privacy have always been things that the industry and the general public need to work together on, and I also ask consumers to have more desire to understand technology and more trust.

Before this, the car manufacturer needs to do a good job in the network security design of its own relevant system, and the industry needs to work together to standardize the boundaries of each type of technology.Just like every smartphone has a front camera, technological, industrial, and societal progress is an unstoppable force. As an algorithm supplier, MINIEYE is a participant in this progress and hopes to contribute to the safe implementation of technological products. We have experience and know the risks involved in the entire chain. However, the power of a single party is insufficient to drive the entire ecosystem forward. It requires the collaboration of technology suppliers, representatives from car manufacturers, and representatives of consumers to establish clear boundaries for technology.

G: Indeed, this is something that needs a collective effort to be determined. Are there any viable specific approaches? I have noticed that MINIIEYE has collaborated with 360 before.

Y: Yes, MIINIEYE and 360 are collaborating in the field of network security to explore ways to prevent network attacks.

As mentioned earlier, within our own technical framework, neither images nor videos are saved, and even in the local environment, the linkage between data and functionality is discarded after use. Our approach is to convert facial images into 512-dimensional encrypted files through the network. Not only is it impossible to restore the photo, but it also cannot be recognized from external technical systems who the subject is.

In fact, car manufacturers are more concerned about consumer sentiment. In reality, consumers need a sense of psychological security more than actual technical and network security. Many people would not want a conspicuously placed camera in their field of vision, as it creates an invisible sense of pressure. Even before concerns about privacy collection and leakage, the appearance of a visible camera makes people uncomfortable.

For example, last year we exhibited a car screen along with another supplier that adopted a solution with an underscreen camera, with the algorithm provided by us. From the overall perspective, the camera is completely invisible to the naked eye, and even the cut coating is made very concealed, creating a good visual experience.

Of course, manufacturers have an obligation to explain the existence of the camera to consumers. But from a psychological perspective, as long as it doesn’t appear in the field of vision, people won’t feel strongly resistant.

Many people use stickers or other things to cover their laptop cameras physically, as a naive form of resistance. I used to do it too, but it’s just a psychological resistance. Everyone’s smartphones also have front cameras, but we don’t cover them, right? This is because the general public has accepted their existence.

The phone is not a problem, but the cameras in computers and cars can make people alert. This is actually a very natural physiological defense mechanism. However, these are not entirely within the scope that technology can solve. Therefore, everyone’s efforts in product design and guidance in concepts and ideas still have a long way to go.

In conclusion

Perhaps it’s because I’ve been forced to work from home for too long, and I’m just bored. At least I didn’t think clearly before this interview, why do car companies still flock to car cameras that seem to cause more trouble than benefits. Even like many people, I think that this is just a demand invented by product managers under the pressure of KPI.

However, the fact is not what I think.

The world’s major automotive countries and regions all push regulations to lead, to better protect the lives and safety of drivers and passengers in the car from distracted and tired driving behaviors.

Whether it is 2D or 3D, visual or radar, car companies and suppliers are constantly exploring and laying out through different technological paths, trying to bring more to consumers.

After the wild growth of the Internet, the public’s awareness of data security has completely awakened, and the saying of “willing to use privacy for convenience” in the words of big factories no longer holds water. From the implemented “Data Security Law of the People’s Republic of China” to the EU’s GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), countries, society, the public, and manufacturers are still moving in a good direction. However, they are still a bit like each other.

Whether it is the coincidence of horror lines suddenly appearing in audio content played in the car or the seemingly unreasonable function of car cameras, they always become social hot news. Even after the storm, they will often be mentioned and urged by the media. These things invisibly deepen the public’s distrust of new technologies.

The motivation and original intention are good. Now it seems that facing the simple demands of the society, the most lacking thing in the industry is effective communication with consumers and public opinion, and the driving force to establish standards.

I believe that before the end of the third decade of the 21st century, the vast majority of people will drive cars with in-car cameras. Before that, there is still much to be done to make people not reject, but more naturally accept their existence and the technology behind them, from society to the industry.

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.