Ao Ao Hu

From the pure belief in new energy to the fuel-based independent factories, the extended-range power that was once ridiculed as “taking off pants and farting” has now become the common straw that both parties reach for in different ways.

Putting aside the ideals of the old players and the support of Huawei, the two new forces with the strongest momentum this year, NETA and LI, have joined the extended-range luxury lunch. Geely has just launched the Star Way L extended-range electric version, Changan’s sub-brand, Deep Blue, directly chose the extended-range, and Great Wall had a heated discussion about “extended-range vs. DHT PHEV” mid-year.

If we add the rumor of XPeng’s development of extended-range power a while ago (later denied by the official), besides NIO, which has a battery swapping system, many well-known domestic manufacturers, both new forces and traditional independent brands, have some kind of connection with the extended-range (or the word “extended-range”).

Once You Have Extended-Range, You Have Electric Power

Although it was named the “extended-range electric version,” the new Star Way L version is not equipped with pure extended-range power like Ideal and Huawei. Its power system still uses Geely’s Thunderbolt Hi-X DHT hybrid technology.

Geely used to add the “Hi-P” suffix to indicate “PHEV based on Thunderbolt Hi-X.” In the case of the Star Way L, maybe because the PHEV version adopted a large battery configuration with a range of 205km, in order to highlight the practical value of the extended-range model enhanced by the large battery and simplify understanding and memory, it changed the name to “extended-range electric version.”

Geely isn’t the only one struggling with the names of “PHEV” and “extended-range.” A few months ago, Wei Jianjun, the CEO of Great Wall, and Yu Chengdong, argued about “who is more advanced between PHEV and DHT.” Earlier, Voyah held a special briefing to explain why the second model had changed from extended-range to “multi-mode drive” (PHEV).

Geely named PHEV “extended-range,” Great Wall argued that PHEV was not inferior to the extended-range, and Voyah had to explain to users why it did not use the extended-range, all because the public seems to believe that “the extended-range is superior to PHEV” in terms of electrification. After all, electrification has become almost a symbol of “advanced,” and “PHEV” is a former name that was once uninspiring for many years.The cognitive bias can be traced back to the debate over whether it is “range-extender hybrid” or “range-extender electric”.

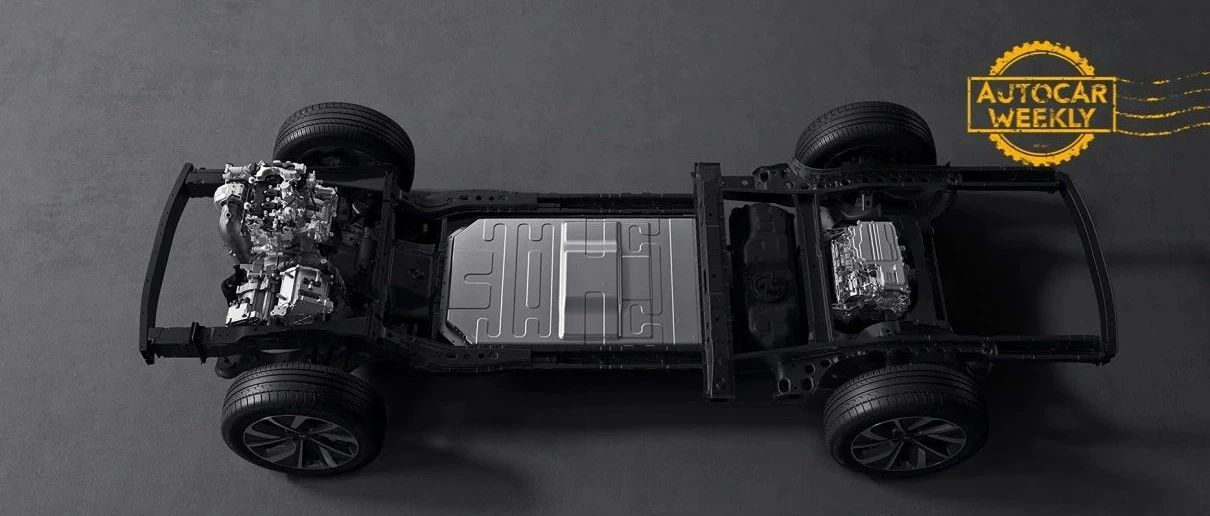

The pure range extender drive and the various series-parallel DHT hybrids have been talked about for two years. Simply put, the fundamental difference between a true range extender, such as the Ideal, Deep Blue, and Lanteng FREE, and series-parallel DHT hybrids, such as Lightning God Hi・X and Lemon DHT, is whether the internal combustion engine can directly drive the wheels, in other words, whether it has direct drive capability.

In a range-extender powertrain, the internal combustion engine never directly drives the wheels, while in a series-parallel DHT hybrid, the clutch can be opened and closed to switch between series (range-extender) and direct drive/parallel. Of course, because the series-parallel DHT has direct drive capability, it may incorporate various mechanical gear mechanisms, while range extenders do not require mechanical gears.

The problem lies in the fact that because the range extender always drives the wheels with an electric motor, it seems to have the right to call itself an “electric vehicle” or a “range-extender electric vehicle,” while plug-in hybrids, regardless of how they are configured, ultimately belong to the “plug-in hybrid” category.

In today’s Chinese internet world, “range-extender electric” is more commonly used than “range-extender hybrid”. So in the consumer’s perception, range-extender = “range-extender electric” ≈ electric vehicle, while DHT plug-in hybrids = (ultimately) plug-in hybrids = hybrids ≈ fuel vehicles.

The technical difference between series-range-extender hybrids and series-parallel DHT hybrids is only the difference between direct drive capability or not, but such a subtle difference has evolved into a “electric vehicle” vs. “non-electric vehicle” identity chasm.

Range-Extender Electric? Range-Extender Hybrid?

The boundary of “electric vehicle” is actually a mess. Some people believe that it should be defined by the “source of energy (onboard)”: as long as it is still “possible” to burn fuel (regardless of whether it is “necessary” or not), any new energy vehicle equipped with an internal combustion engine should not be called an “electric vehicle”. Therefore, range extenders should be called “range-extender hybrid”.Some people believe that the classification of a vehicle should be based on its “driving mode”: if the wheels are directly and always driven by motors, the vehicle can be called an “electric vehicle”. Therefore, the range extender should be called an “extended-range electric vehicle”, while the parallel/series hybrid DHT can only be called a hybrid because it can be driven directly by an internal combustion engine.

Currently, based on the popularity of the term “range extender electric vehicle” and the fact that Geely and Great Wall have to resist the pressure of the term or make use of the term to describe their vehicles, the second definition is currently occupying the majority of people’s minds.

However, this is questionable, as the biggest problem lies with the “ancestor of the range extender”. Currently, all new range extender vehicles at home belong to PHEV with a large battery. However, range extender HEVs with small batteries do exist, such as Nissan’s e-POWER. The e-POWER does not have an external charging function, and the battery with single-digit kWh hardly supports pure electric driving in the true sense. However, as a range-extending driving technology, its wheels are always driven by motors. If judged by “driving mode” rather than “energy source”, the e-POWER is undoubtedly an “electric vehicle”.

It is somewhat funny to call an HEV, which depends solely on refueling and cannot be charged externally, an “electric vehicle” only because its wheels are always driven by motors.

Imagine if there were a memory replacement magic that replaced “range extender electric vehicle” in the minds of 1.4 billion people with “parallel hybrid”, would there be battles within the range-extending camp on who is more advanced even in the case of complex parallel/series hybrid DHT vehicles that have to rely on the name of “range extender” for promotion?

Traditional automakers, except for Changan Shenlan, who took a series hybrid range extender route, also emphasize the “range-extending” property of their big-battery PHEVs, as do Geely, Great Wall, and other parallel/series hybrid DHT hybrids. Wei Pai wants to “make it clear,” while Geely’s “range-extender version” is “if you can’t explain it, just join it.”On the side of new forces, for new force brands like Zero Run, NIO, and ZYOYO, PHEV, as an understood “electric vehicle,” is a choice “sacrificing” the minimal brand image for a much broader market space, especially in today’s environment where the cost of lithium-ion battery is soaring.

Even for new brands like Leading Ideal (Li Xiang) and Deep Blue, which rely on traditional factories, compared with other types of plug-in hybrids, PHEV is not only more “electric” and “new” in terms of image, but also more flexible in the relative position of the PHEV system and the driving wheel. The new platform can better take care of the pure electric version. This not only adds to the competitiveness of the pure electric version, but also prepares for the future.

For these brands, PHEV is certainly an ideal choice for “compatibility with non-pure electric vehicle users,” but it is difficult to believe that the sales will double.

On the positive side, so far, except for Ideal, the PHEV camp has no other successful models yet. The circle of PHEVs has benefited largely from Huawei’s endorsement and the core competitiveness of the vehicle-machine ecosystem. The market performance of Leading Ideal’s FREE can only be described as mediocre, and Skywell, which came earlier, has basically faded out of the head position, not to mention the self-disbandment rumors of ZYOYO recently.

However, Leading Ideal itself has emerged from being mocked and misunderstood. This is a case of tit-for-tat, and even today, even though there are more PHEV models than Ideal currently, people still think of Leading Ideal when they mention PHEV. At first glance, it seems that PHEV has gained public familiarity and recognition, but perhaps it is only Ideal itself.

On the contrary, we have always overlooked the heaviest player in the PHEV market, BYD. From last year to this year, the DM-i momentum is unstoppable. With DM-i, BYD itself easily broke pure gasoline-powered cars, while the market share of PHEV in the whole market is close to 1/4. They almost dominate everything.

But how many ordinary consumers know that DM-i, as the simplest series-parallel DHT hybrid, is actually closer to PHEV than the similar hybrid technology of Geely and Great Wall? DM-i never claims to be related to PHEV, but has also achieved sales miracles no less than Ideal ONE in those years.Therefore, whether it is a real series-parallel plug-in hybrid, or a series-parallel DHT hybrid with range-extending properties leveraging the name of “range-extending”, “range-extending” is neither a necessary condition for market myth nor a sufficient condition for success or failure to be specific in this context.

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.