Author: Zhu Yulong

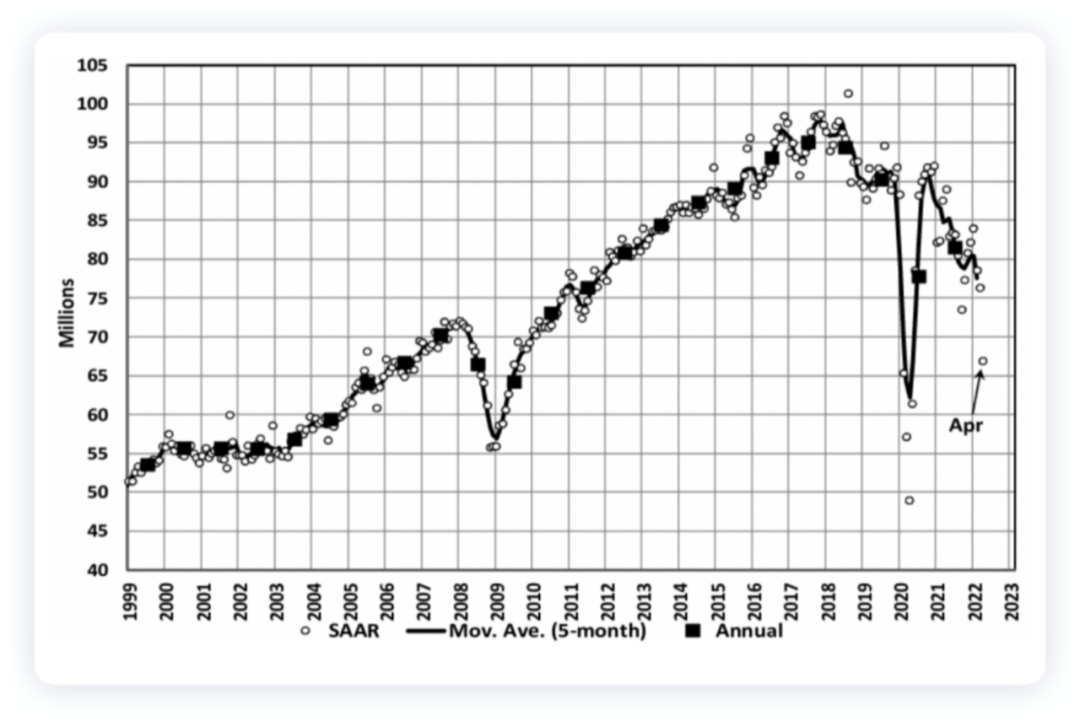

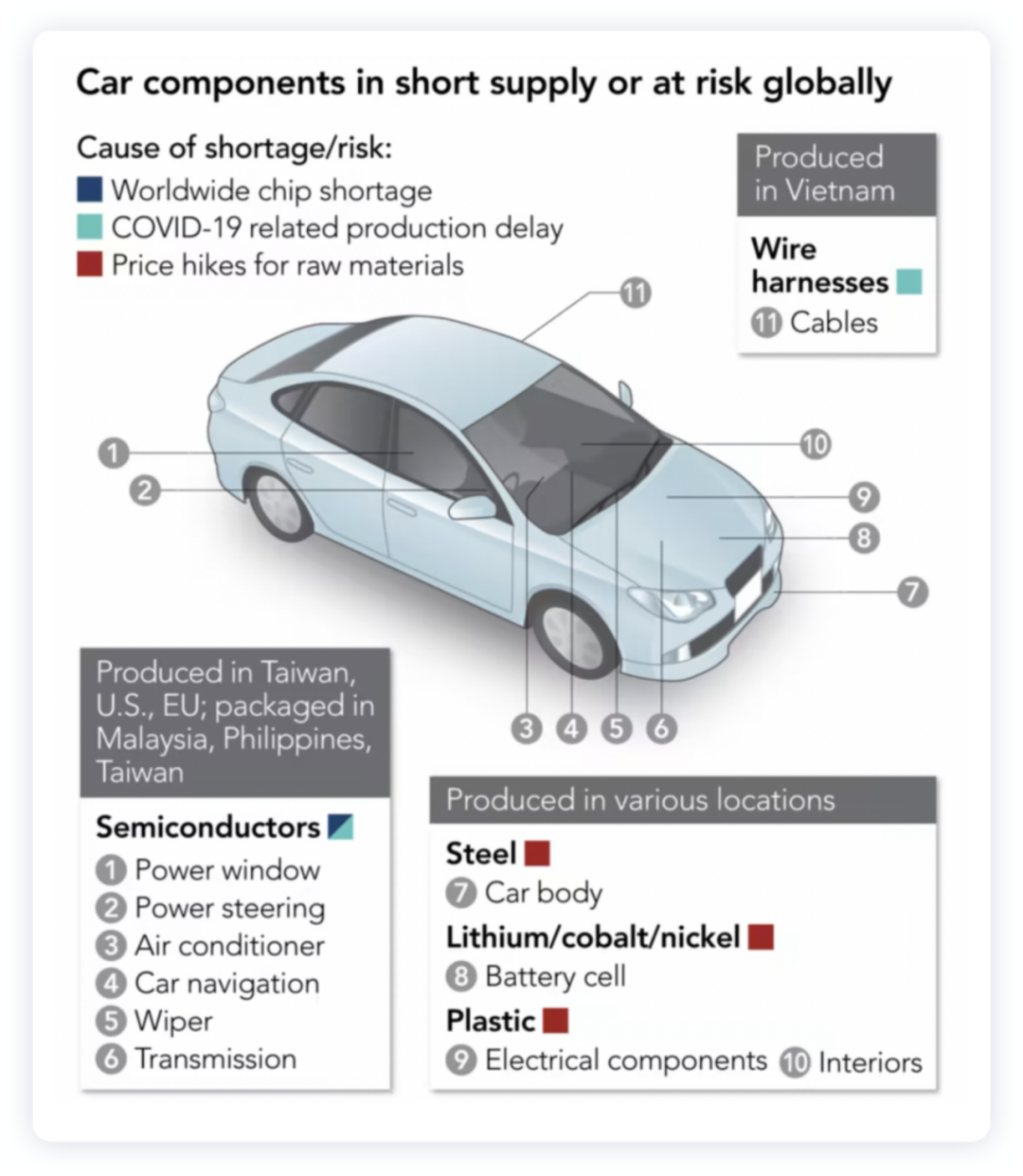

From the end of 2020 to May 2022, since the outbreak of the pandemic, the automotive industry has been the most severely and longest affected industry by the global chip shortage. The problem of automotive chip supply shortage has gone through issues such as 8-inch wafers, TSMC’s manufacturing weight, and packaging in Malaysia. Both the media and the government mainly directed their criticism towards chip companies and the industry itself, leading to issues such as:

-

The belief that chip companies shifted their resources and production capacity towards smartphone and computer chips.

-

The transition from IDM to chip foundry had the industry investing insufficiently in manufacturing capacity.

-

Tier 1 electronic suppliers had slow response times and insufficient ability to respond to changes in demand due to supply chain opaqueness.

-

Car factories were too insistent on low inventory and just-in-time (JIT) systems, leading to major disasters during the severe automotive chip shortage.

During the development of the automotive industry and in anticipation of the next era, new manufacturing and supply chains have emerged, revealing structural weaknesses and flawed methods (which were not previously issues) that have made it clear that increasing chip production capacity is not a solution to the supply chain crisis plaguing automotive companies.

Three Driving Modes Supported by Tesla’s Safety System

If in 2021, it was acceptable to place more blame on chip companies, come 2022, we need to look into the internal processes and project management within automotive companies to determine when this supply chain crisis was triggered due to the pandemic and chip shortage.

Note: When the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami hit the automotive industry, Japan and global automotive companies faced several months of production tension. From this lesson, Japan’s automotive industry further extended its supply chain to Asia, and companies such as Toyota even began to reserve some key components. Enterprises like General Motors also learned their lesson, but by 2022 it is clear that this is not sufficient.

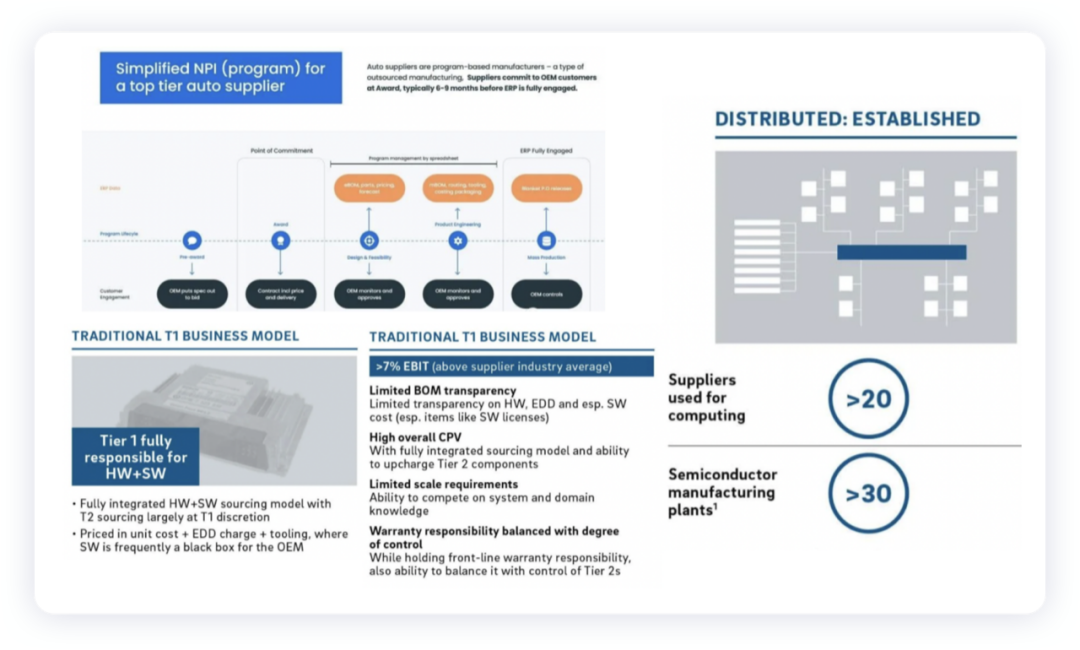

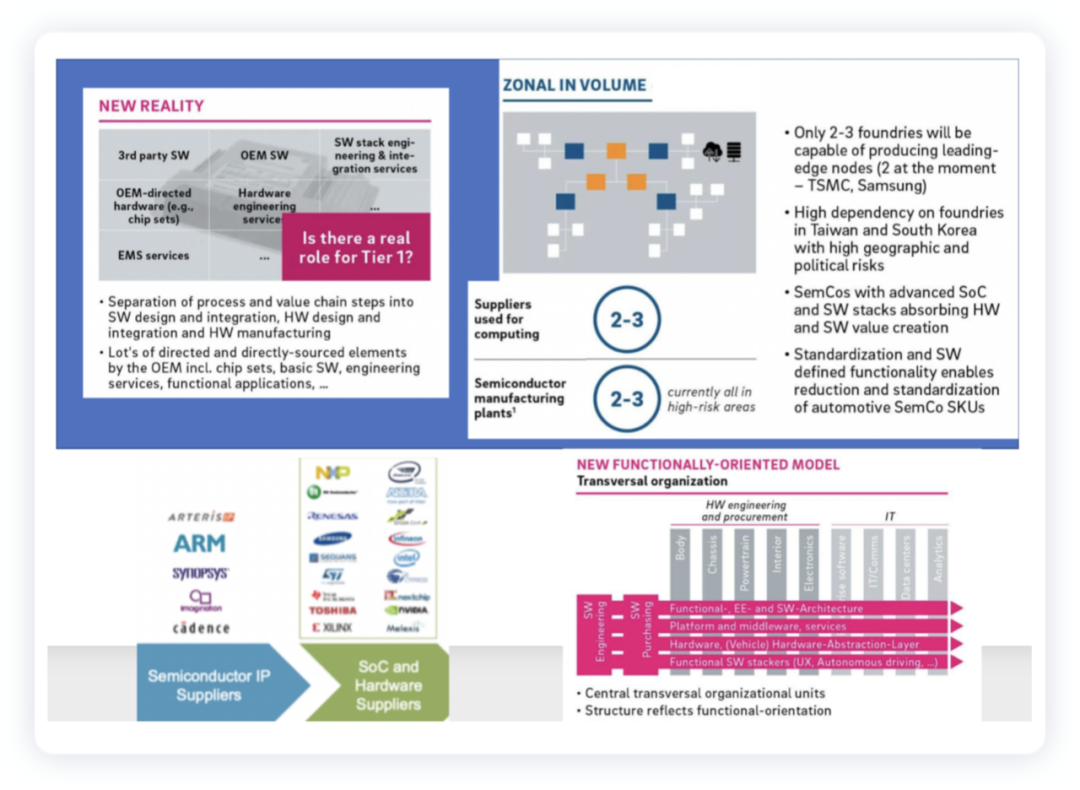

From the current situation, it seems that in terms of ECU and electromechanical components, automotive companies heavily rely on Tier1 suppliers. In the automotive industry, Tier1 suppliers do not independently design or produce ready-made products. Over the past 20 years, Tier1 has bid on contracts with automotive OEMs to provide the required customized parts. Suppliers meet the ECU automotive parts specified by the automotive OEMs through the demand of SOR and their own basic designs. From the overall historical perspective, most global automotive companies have entrusted the procurement of components in the electronic ECU of automobiles, the manufacture of ECU, the selection of chip manufacturers, and the verification and confirmation of subsystems to Tier1 to achieve their goals. From the perspective of automotive OEMs, they mostly order “functionality” from automotive Tier1 through features and components. In fact, over the past 20 years, with the deepening of modularity, the success of the new car development of global automotive companies (except for players like Tesla) is increasingly dependent on their suppliers’ project management capabilities to meet the automotive OEM’s budget and deadlines.

From the current situation, it seems that in terms of ECU and electromechanical components, automotive companies heavily rely on Tier1 suppliers. In the automotive industry, Tier1 suppliers do not independently design or produce ready-made products. Over the past 20 years, Tier1 has bid on contracts with automotive OEMs to provide the required customized parts. Suppliers meet the ECU automotive parts specified by the automotive OEMs through the demand of SOR and their own basic designs. From the overall historical perspective, most global automotive companies have entrusted the procurement of components in the electronic ECU of automobiles, the manufacture of ECU, the selection of chip manufacturers, and the verification and confirmation of subsystems to Tier1 to achieve their goals. From the perspective of automotive OEMs, they mostly order “functionality” from automotive Tier1 through features and components. In fact, over the past 20 years, with the deepening of modularity, the success of the new car development of global automotive companies (except for players like Tesla) is increasingly dependent on their suppliers’ project management capabilities to meet the automotive OEM’s budget and deadlines.

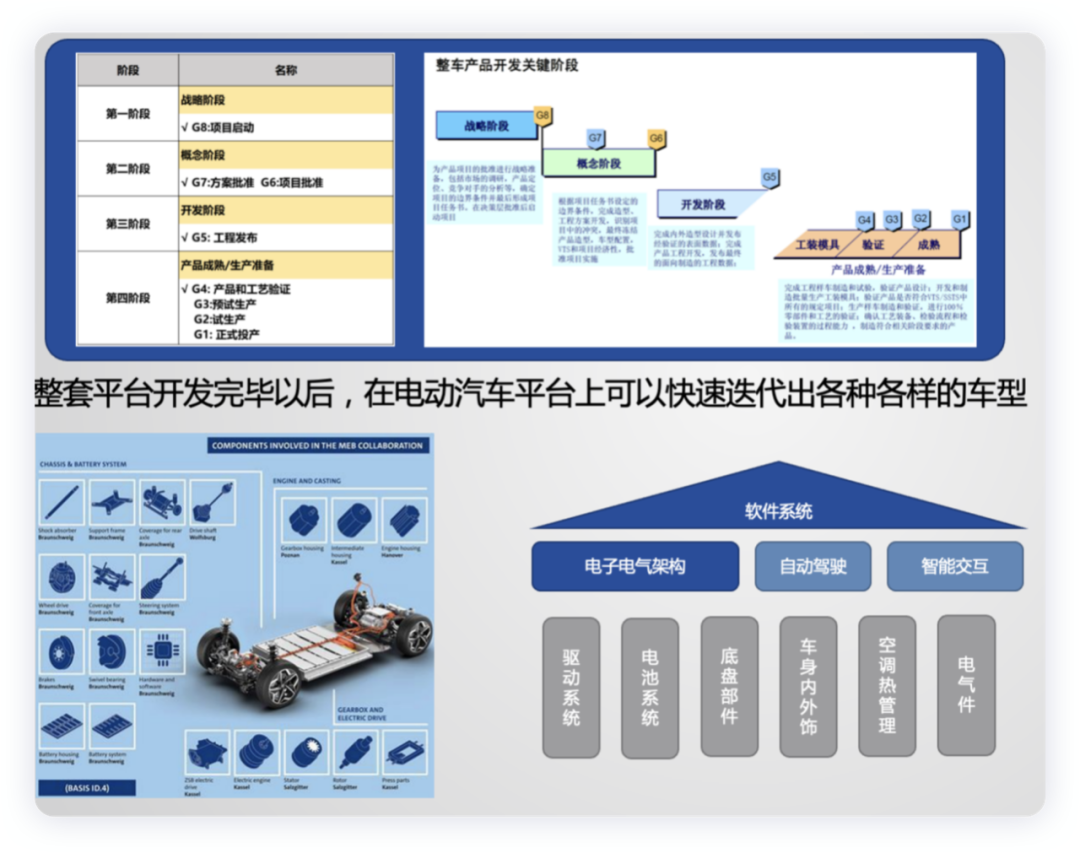

If we look at the evaluation of the current status of automotive supply chain visualization and project management through the perspective of the chip problem, there are a lot of interdependent relationships in the construction process of the distributed system. In other words, this is a kind of subcontracting system. In the past 30 years, the work of Tier 1 upstream departments, including procurement, engineering, and quality, was actually shielded from automotive companies. That is to say, the controlled departments of automotive companies corresponded to project teams within Tier 1, which were updated by automotive companies and suppliers through spreadsheets and whiteboards. With the introduction of new functional requirements in automotive electronics and the technological changes brought by digital functions required for electrification and autonomous driving, the entire communication includes hardware, software, mechanical, electrical, functional safety, information security, and industrialization.

From the perspective of tracing back to the beginning of automotive electronics, the final process from top to bottom will include automotive OEMs, Tier1, and even Tier2 and Tier3 combined. Previously, we saw that foreign automakers imported a large number of IBM Rational DOORS (Dynamic Object-Oriented Requirements System) to replace the original Word and Excel. This type of process culture has begun to migrate downward. Process, tools, and project management require changes when developing a complex system.

In addition, what’s interesting is that with the next step of focusing on integrated architecture, the normal car companies start with the selection of SoC chips and directly negotiate cooperation, such as the previous cooperation between Volkswagen and Qualcomm.

Transparency and Contract Manufacturing Model brought by Tesla

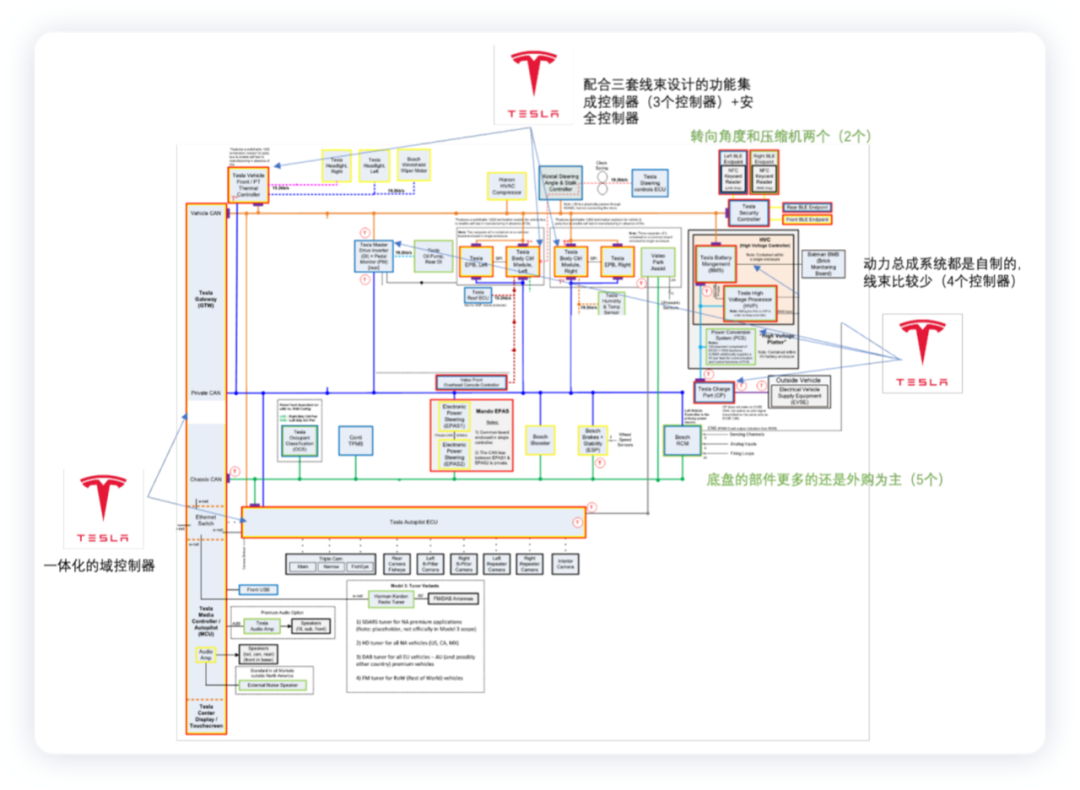

Currently, the major logic behind the changes in Tesla’s automotive electronics mainly revolves around the restructuring of various automotive electronic modules. Even TPMS and Bluetooth keys are gradually selecting trusted chip suppliers and handing them over to contract manufacturing (EMS) enterprises for processing. That is to say, in Tesla’s automotive electronics, except for the BOM lists of limited suppliers, all major chip suppliers are penetrated.

When combined with Tesla’s manufacturing of subsystems completely in unit manufacturing and realizing rapid whole-vehicle manufacturing in the new factory, my understanding is that not only software but also the combination of digitalization and chip selection, has been taken to a very far level by Tesla. In the new generation of intelligent EVs, not only software and cloud capabilities are constructed, but also the control over electronic chips is very strong. This ability is fully designed and docked with chip enterprises. My understanding is that the NPI process for new designs in automotive electronics has been internalized.

In summary, I think that it is currently impossible for the global automotive industry to achieve internalization of the NPI process for new functions like Tesla does, and modular innovation at the manufacturing level. However, this chip crisis has actually accelerated the transparency and contract manufacturing of the entire electronics supply chain. The simplest thing is that all major long-cycle chip BOMs of Tier 1 may need to be evaluated by OEM procurement and supply chain engineers.

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.