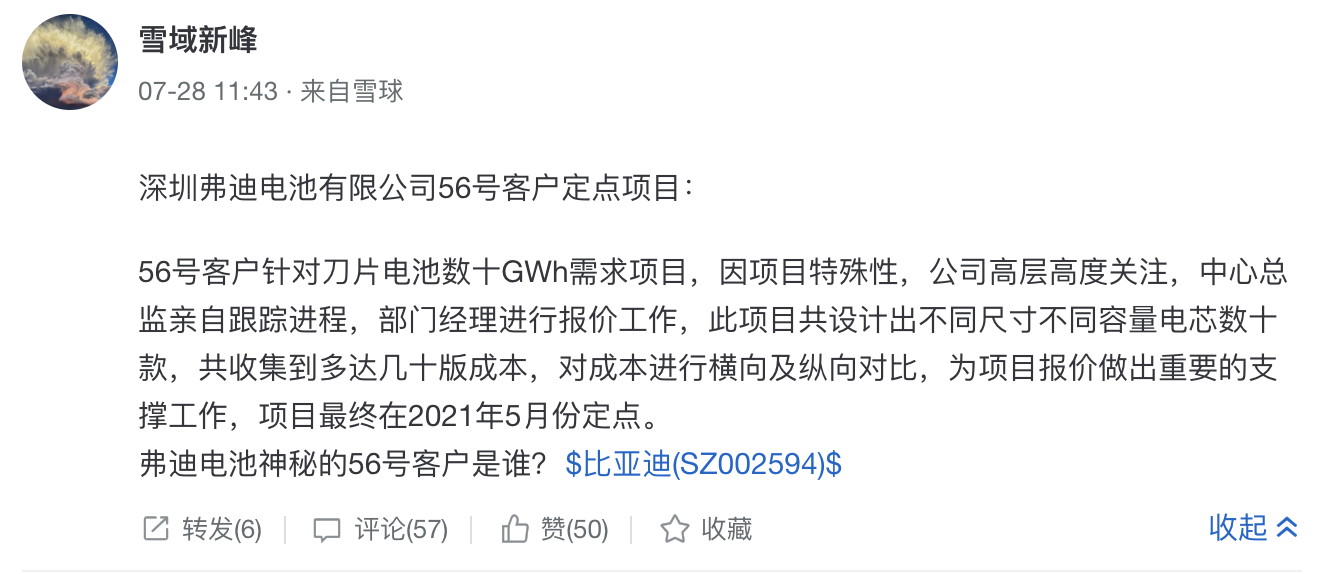

On July 28th, a piece of information about customer 56 from VD factory was exposed by Snow Mountain New Peak, a snowball user, causing a sensation in the stock group.

According to the message, customer 56 made an astonishing demand for “dozens of GWh” in “blade battery” supply, and BYD’s top management attached great importance to the project, which was finally designated for customer 56 in May.

As for the question “who is customer 56”, I have already made my guess in the title. In addition to exploring the guess in detail, we will also discuss another question: has BYD ushered in a period of take-off?

Why Tesla?

Because the customer’s demand is “dozens of GWh”, and the battery is iron phosphate.

In the whole year of 2020, BYD’s annual installation volume of new energy vehicles and storage batteries, including pure electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids, was 12.6 GWh, based on the sale of 130,970 pure electric vehicles and 48,084 plug-in hybrids.

As a comparison, in 2020, Tesla topped the global rankings of new energy passenger vehicle sales among car companies, selling 499,550 cars, followed by Volkswagen with 212,000 cars, BMW with 192,646 cars, BYD with 179,054 cars, and SAIC-GM-Wuling with 174,005 cars.

Assuming that this “dozens of GWh” is 30 GWh, if this customer 56 is not Tesla, then this battery order can almost meet the power battery demand of any of the top 5 host manufacturers’ new energy vehicle sales in 2-3 years. We can also analyze the top five car companies.

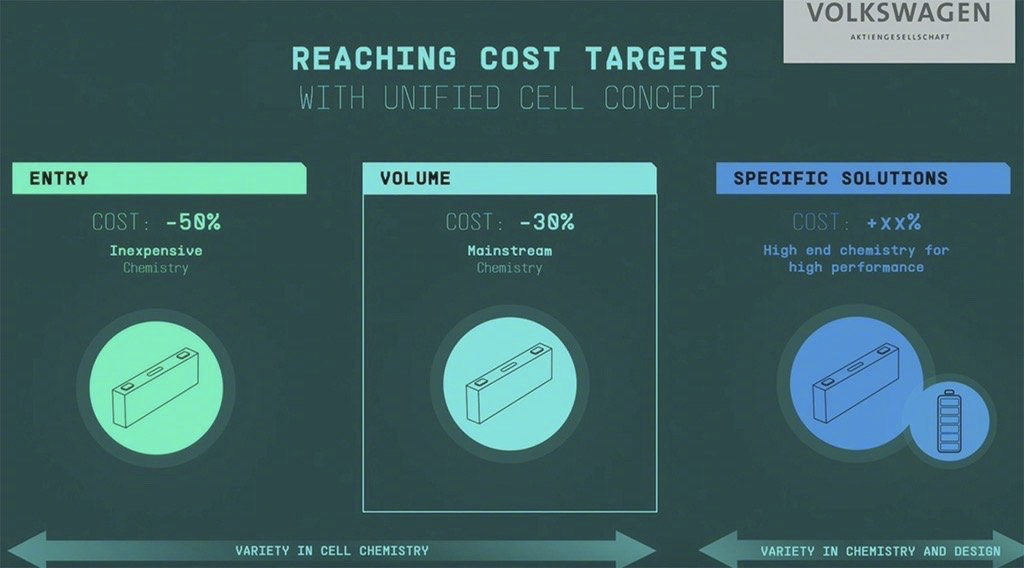

Volkswagen: Blade is not “standard”

For Volkswagen, this year is the first year of mass delivery of MEB models globally. Existing power battery orders have been settled. Volkswagen’s main battery suppliers for ID. series in China are Ningde Times. The two companies have also established several joint ventures, such as Time FAW, Time SAIC, and SAIC Times, and have established a good and stable battery supply relationship in the past few years. It is against common sense to infer that Volkswagen signed a huge battery order with BYD in the starting stage of ID. series new cars.

# MEB platform emphasizes compatibility and sharing in order to increase efficiency and lower costs by reducing differences technically. Volkswagen Group also stated on this year’s Power Day that they will adopt standardized battery cells and fully implement them by 2023. Since BYD’s “Blade Battery” does not fit into this strategic direction, it is impossible for Volkswagen to place an order of tens of GWh.

# MEB platform emphasizes compatibility and sharing in order to increase efficiency and lower costs by reducing differences technically. Volkswagen Group also stated on this year’s Power Day that they will adopt standardized battery cells and fully implement them by 2023. Since BYD’s “Blade Battery” does not fit into this strategic direction, it is impossible for Volkswagen to place an order of tens of GWh.

SAIC-GM-Wuling: Matching Production with Demand

After excluding Volkswagen, we look at SAIC-GM-Wuling. Currently, the electric vehicle sales of SAIC-GM-Wuling mainly depend on Hongguang MINIEV. For this small car with a battery capacity of less than 14 kWh, 1 GWh of battery is enough to produce more than 70,000 cars. With a recent monthly sales volume of around 30,000 units for Hongguang MINIEV, 10 GWh is enough for two years.

The total sales of Baojun’s electric vehicles last year were 46,354 vehicles. Calculated by an average single car’s 30 kWh of available battery capacity, 10 GWh is enough for seven years.

Therefore, with Ningde Times and Guoxuan High-tech already supplying batteries, dozens of GWh orders for SAIC-GM-Wuling are beyond reason.

BMW: No Need for It

Next, let’s talk about BMW. In China, BMW has also established a stable supply relationship with Ningde Times. Due to the relatively high positioning and performance-oriented requirements of its electrified products, BMW is currently using high-density ternary lithium cells, with 80 kWh for iX3, and 83.9 kWh for i4. The even higher iX uses a 111.5 kWh ternary lithium cell, and it is difficult for lithium iron phosphate batteries to meet such requirements.

BMW will also launch pure electric vehicles in the 5 Series and 7 Series over the next period, still emphasizing high-density and long battery life principles. Whether it is from incremental demand or product positioning, BMW does not seem to be a client of these dozens of GWh lithium iron phosphate batteries.

Inferring Customer No. 56 from the Order

Excluding these manufacturers, the possibility of other manufacturers with lower sales rankings buying this order for dozens of GWh of lithium iron phosphate batteries is even smaller. Conversely, we can deduce that Customer No. 56 probably has the following characteristics from the lithium iron phosphate battery and order of dozens of GWh:

- A low-end product line of lithium iron phosphate batteries with demand that currently exists or will be introduced soon.

- The customer has a total demand for power batteries in the short term that exceeds dozens of GWh.At this point in time, only Tesla can simultaneously meet these two requirements worldwide. Then we need to figure out another question: Why does Tesla use BYD’s batteries?

Meeting Each Other’s Needs

Tesla’s Far-sightedness

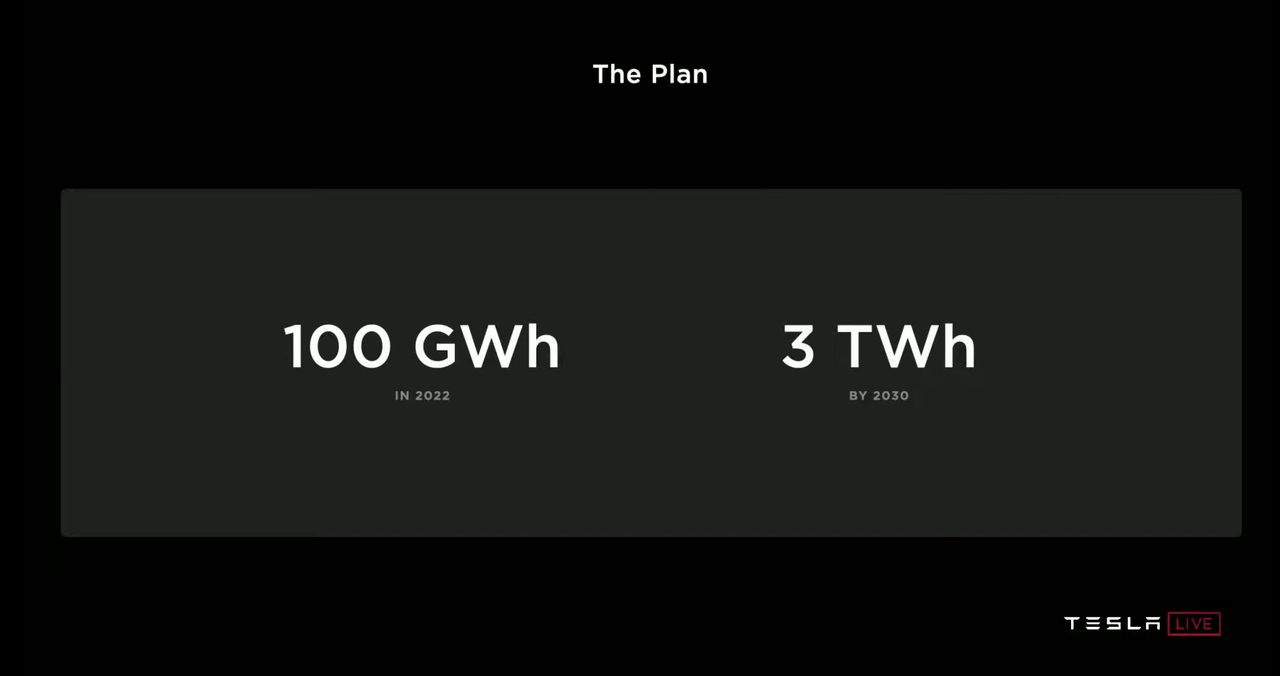

At Tesla’s Battery Day in September 2020, Musk expressed the view that Tesla’s battery demand will reach 3,000 GWh by 2030, which is much more than the capacity of Panasonic, LG, and CATL who combined could supply the batteries. Therefore, Tesla needs to build its own battery factory on the basis of purchasing batteries to supplement capacity.

On the basis of delivering 499,550 cars in 2020, Tesla expects to continue to maintain an average annual growth rate of about 50% in the coming years. It is estimated to deliver over 750,000 cars this year and over 1 million cars in 2022.

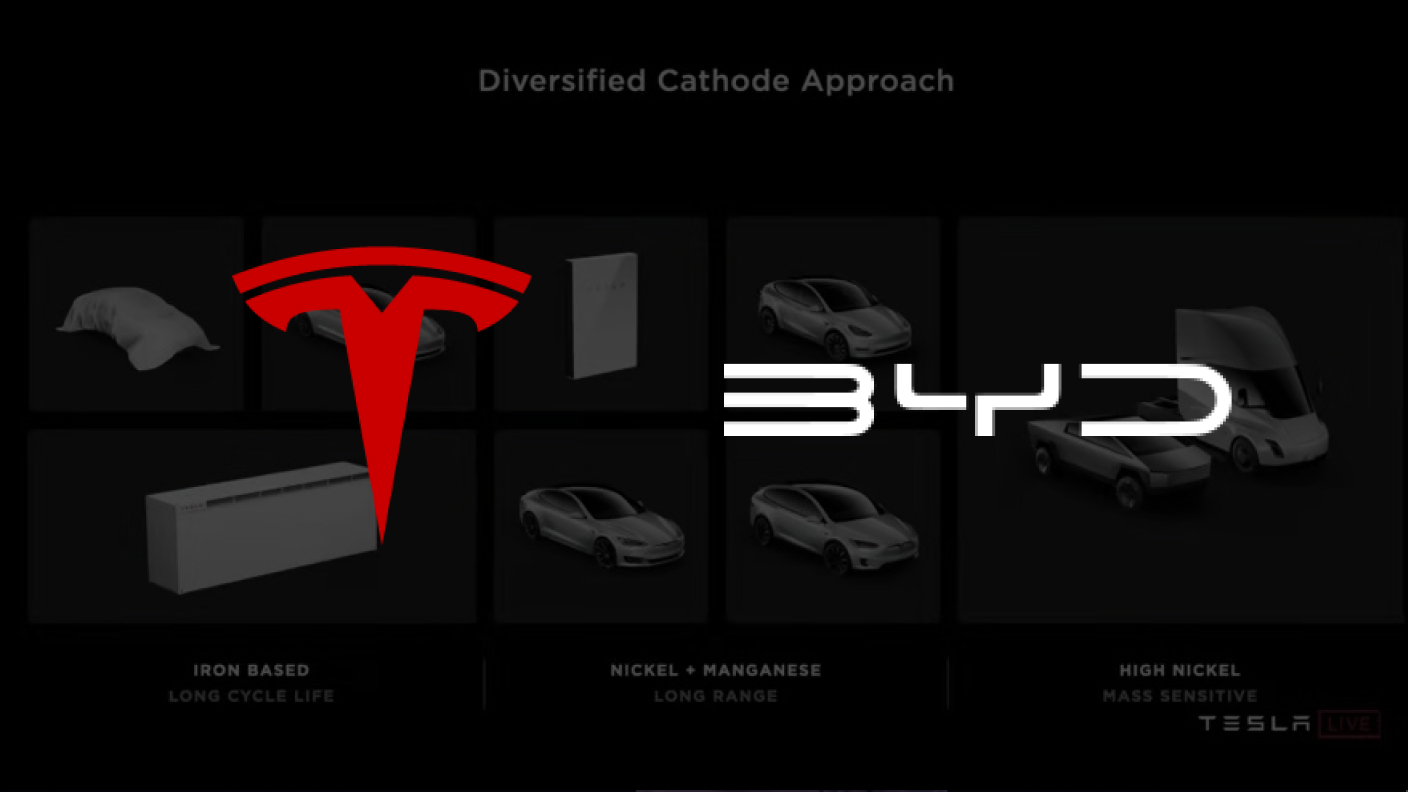

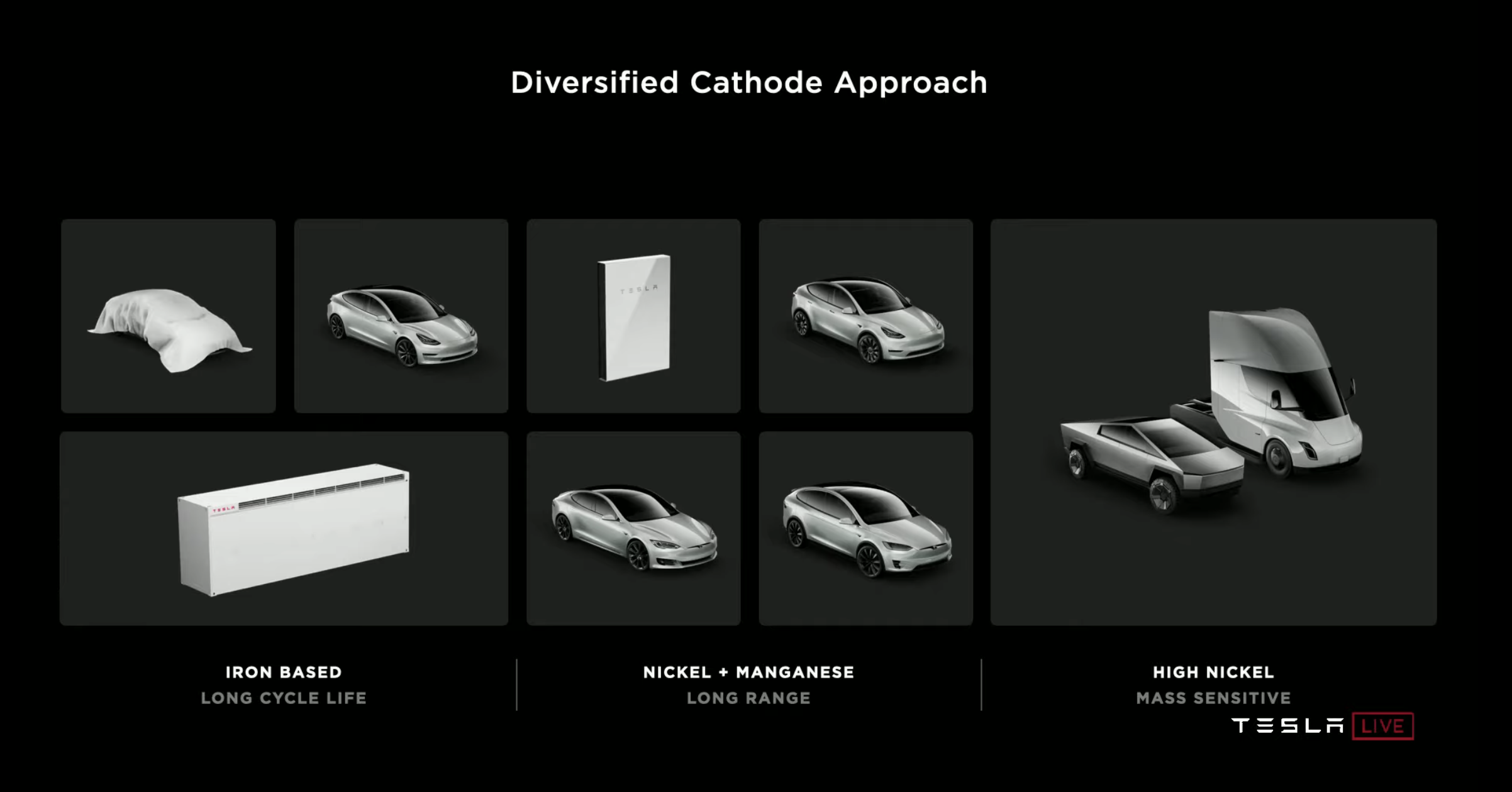

Then let’s take a look at Tesla’s product line and battery plan: Vehicles on the right, such as Semi and Cybertruck, which pursue long-range driving, require batteries with the highest energy density, so they will adopt high-nickel lithium batteries; Model S/X in the middle and products such as home energy storage have a lower requirement for cell energy density, so they use nickel + manganese lithium cells to achieve longer range; The energy storage power station on the left and entry-level electric vehicle products will adopt lithium iron phosphate batteries, which have a long cycle life and the lowest cell cost.

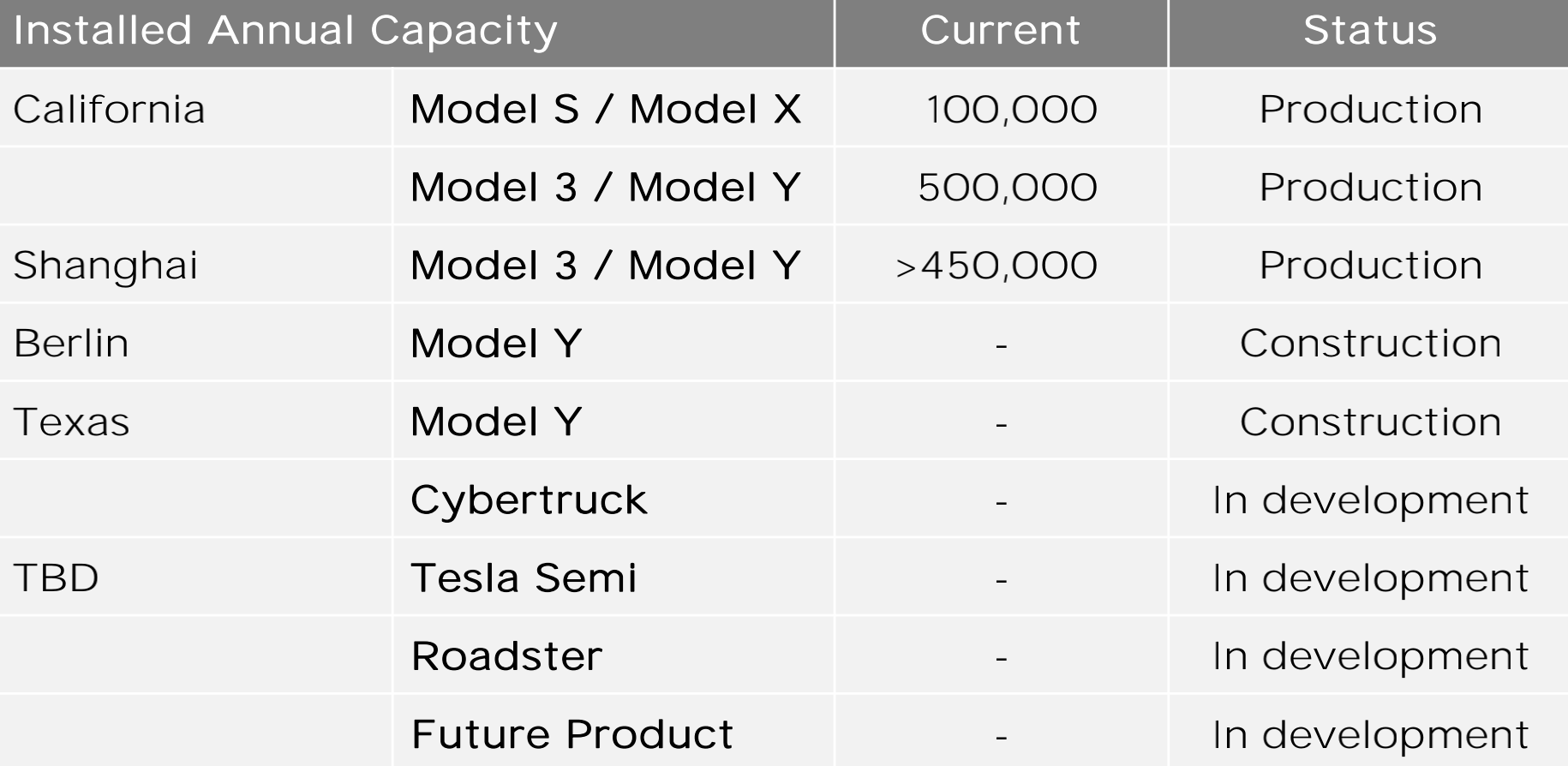

At present, Tesla has two factories in operation worldwide, Fremont factory and Shanghai factory, with a maximum production capacity of over 950,000 Model 3/Y per year.

The yet-to-be-completed factories to be put into production are in Texas and Berlin. Berlin factory is only used to produce Model Y, and the expected production capacity is 500,000 cars per year. Texas factory will produce Cybertruck and Model Y, with a total expected production capacity of 1 million cars per year. Model Y will be produced first.

The preparation for the further delivery of Tesla’s Model 3/Y has been ready in the factory, where the product line represented by the entry-level products on the left, especially Model Y, will be the main source of growth in the future, and these products all require lithium iron phosphate batteries. Tesla has also publicly stated its sales expectations for Model Y: surpassing the total sales of Model S/X/3 and becoming the best-selling single model globally between 2022 and 2023. For reference, the annual sales of the current best-selling single model globally, Corolla, is about 1.5 million units per year. Assuming that Model Y achieves this goal, with 80% of them being lithium iron phosphate models with a single vehicle capacity of 60 kWh, the annual demand for lithium iron phosphate batteries for only Model Y will be 72 GWh.

The preparation for the further delivery of Tesla’s Model 3/Y has been ready in the factory, where the product line represented by the entry-level products on the left, especially Model Y, will be the main source of growth in the future, and these products all require lithium iron phosphate batteries. Tesla has also publicly stated its sales expectations for Model Y: surpassing the total sales of Model S/X/3 and becoming the best-selling single model globally between 2022 and 2023. For reference, the annual sales of the current best-selling single model globally, Corolla, is about 1.5 million units per year. Assuming that Model Y achieves this goal, with 80% of them being lithium iron phosphate models with a single vehicle capacity of 60 kWh, the annual demand for lithium iron phosphate batteries for only Model Y will be 72 GWh.

In addition, in 2023, Tesla also plans to produce and sell a compact car priced at $25,000. This car, which is already in close planning and is highly likely to be produced at the Shanghai factory, will also use lithium iron phosphate cells. In short, Tesla will have a huge demand for lithium iron phosphate cells in the coming years.

Now let’s take a look at this situation: currently, only CATL supplies lithium iron phosphate cells to Tesla. However, the manufacturers supplying ternary lithium batteries to Tesla have expanded from Panasonic to include LG Chemical and CATL.

From the perspective of Tesla, considering growth expectations, production capacity needs, supply relationships, and bargaining power, having a more stable and competitive supply system during a period of rapid growth is necessary. In the long run, it is not ideal for CATL to be the only supplier of lithium iron phosphate cells. So introducing new suppliers of lithium iron phosphate cells is almost an inevitable occurrence.

Therefore, Tesla’s preparation for lithium iron phosphate batteries is about production capacity, but not entirely about production capacity.

As the domestic automaker that produces batteries by itself, BYD’s appetite is not only satisfied with self-sufficiency. Its goal is to supply batteries to external customers, further improving the scale effect for more industry benefits.

However, since BYD opened up its power battery supply to external customers in 2018, there has been little progress. Regarding energy storage businesses related to batteries, the proportion of second-charged batteries and photovoltaic businesses to BYD’s annual revenue in 2020 was only 7.72%, while in 2019, the figure was 8.22%, and in 2018, it was 6.88%. Progress has been relatively slow.The annual battery installation of BYD, including energy storage business, was 13.4 GWh, 12.3 GWh, and 12.6 GWh respectively from 2018 to 2020, with little substantial progress made. One reason for this is that in previous years, the overall range of electric vehicles was low, and in order to improve range and meet the national new energy subsidy policy’s 160 Wh/kg energy density threshold for 1x subsidy, everyone hoped to use higher-density ternary lithium batteries. Additionally, as a major automaker, BYD’s competitors were also concerned. Under these two objective factors, BYD’s externally supplied batteries were naturally difficult to promote. In sharp contrast, CATL’s installation volume in these three years was 23.5 GWh, 31 GWh, and 34 GWh, ranking first in the world for three consecutive years.

As the gap widened, BYD seemed to be “early to rise and late to bed.” However, BYD’s magical operation in 2020 brought a glimmer of hope to this situation. Speaking of last year’s most impressive marketing case in the automotive industry, it must be the “blade battery.” An insignificant targeted safety promotion combined with independent branding and research made the “blade battery” widely spread and deeply rooted in people’s hearts. During this period, facing off against CATL in blade battery testing further increased the heat of the blade battery. The Han EV equipped with this battery became the best-selling new energy vehicle model of the BYD brand over the past year.

As the industry develops, motor efficiency, battery materials, battery pack structure, and other technologies have rapidly improved, and the overall range of electric vehicles has greatly increased. The industry’s demand for power batteries has also gradually shifted from high density to a balance between cost and performance.

In the first half of this year, the installation volume of lithium iron phosphate batteries in China was 17.38 GWh, up 273% year-on-year, and the market share during the same period increased from 27.8% last year to 37.5%. The advantages of lithium iron phosphate batteries in the mid- and low-range electric vehicle market, where range requirements are not so high, are gradually becoming apparent.

Under this trend, the external conditions for BYD’s battery supply have been basically met. Cooperative agreements from automakers such as FAW Hongqi, Changan, Dongfeng, and Toyota have also raised investors’ expectations for BYD. At the same time, sales of BYD’s new energy vehicles have also rebounded significantly, with over 200,000 sold as of July, a year-on-year increase of 181%.

In the current new energy investment boom since 2020, BYD’s stock price has continued to rise, now surpassing 800 billion yuan, making BYD the number one car company in China and the fourth largest in the world, second only to Tesla, Toyota and Volkswagen.

In the current new energy investment boom since 2020, BYD’s stock price has continued to rise, now surpassing 800 billion yuan, making BYD the number one car company in China and the fourth largest in the world, second only to Tesla, Toyota and Volkswagen.

However, as the saying goes, “there is no rose without a thorn”. As BYD’s stock price hovers around its historical high, at nearly 200 times P/E ratio, if BYD wants to push forward, it will not be able to rely on the likes of Roewe RX5 and Red Flag E-QM5. Investors are looking for a major breakthrough in business.

For example, taking over Tesla’s strongest growth point – power battery orders.

This order for tens of GWh signed with Tesla is not only large in size, but also allows BYD to join the list of Tesla battery suppliers, including Panasonic, LG Chem, and CATL. This is undoubtedly a significant endorsement and recognition for BYD. If the progress goes smoothly, it will also become an important breakthrough for BYD’s external supply of batteries, truly opening up BYD’s battery external supply business.

And as long as the stock price goes up, everything is possible.

Therefore, regarding the rumors about “BYD Customer No. 56”, “the center director personally tracks the progress, and the department manager is responsible for quoting work. The project has designed dozens of different sizes and capacities of battery cells, collected dozens of versions, and conducted horizontal and vertical cost comparisons”, it is not impossible according to this analysis.

In my opinion, signing the power battery order with Tesla is beneficial for both parties, but the significance for BYD is obviously more important. This crucial opportunity can be said to be something that BYD must seize even if they have to make less or no money at all.

However, for an enterprise that combines car production, mobile phone OEM, photovoltaic energy storage business, and rail transit business, such as BYD, there are still many problems that need to be solved.

Is BYD’s soaring period coming?

To answer this question, we need to look back and find out the problems that limit BYD’s soaring. The biggest problem for BYD before 2020 was that the new energy product line was on the wrong track.

Parallel plug-in hybrids as the mainstream

In December 2013, BYD officially released the second-generation ancestor of its hybrid model, the Qin. This plug-in hybrid compact sedan, with a 110 kW electric drive motor and a zero-to-100 km/h acceleration of 5.9 seconds, carried the vision of BYD’s “second takeoff,” opening a new chapter of BYD’s new energy marketization.After the release of the Qin, BYD persisted in the parallel plug-in hybrid route for 8 years, launching multiple plug-in hybrid models such as the Qin, Tang, and Song, and underwent several facelifts and a major upgrade for the entire lineup.

In the early market, there were almost no competing parallel plug-in hybrid models, and BYD achieved good results in the early market by relying on the long battery life of parallel plug-in hybrids. However, the shortcomings of parallel plug-in hybrids under discharge conditions were exposed with the support of the 1.5T, 2.0T engines, and 6-speed DCT by BYD: shifting jerks, significant power drop, high noise, and high fuel consumption.

As the performance of competing models in the same price range gradually improved, the reputation of parallel hybrid models began to decline, and without essential improvements to the user experience, parallel hybrids could not sustain growth after the policy dividends gradually declined. From 2018 to 2020, BYD’s new energy vehicles fell for three consecutive years, and the insistence on the parallel plug-in hybrid route was one of the key reasons.

Moreover, the persistence of BYD in this mistake has brought another problem: missed opportunities for the development of pure electric product lines.

BYD’s promotion mainly focuses on plug-in hybrids, because Wang Chuanfu believes that “electricity for short distances and oil for long distances” is the rational scenario for new energy. During this period, BYD’s pure electric product line was not separated, and new energy vehicle models for C-end consumers were fueled, plug-in hybrids, and pure electric vehicles all made together. However, the pure electric vehicle models that replaced petrol were not only inadequate in terms of endurance, but also had limited space due to the car body layout, and they were priced the highest among the three.

Therefore, apart from the ride-hailing and taxi markets guided by policies, BYD’s pure electric vehicles that deviated from user value have naturally not seen growth in C-end sales.

However, more regrettable than mediocre C-end sales is that BYD, as the most representative new energy vehicle company in China, wasted valuable market gaps.

The result is that in 2012, BYD relied on selling 456,000 petrol cars annually, and after 8 years, in 2020, its annual sales of petrol cars combined with new energy vehicles were 427,000.

In July 2020, at the Han launch event, BYD unprecedentedly promoted pure electric vehicle models as its main products, and all marketing resources were noticeably skewed towards the Han EV model.

Meanwhile, the price of the Han EV was surprisingly only between the Song Pro EV and the Tang EV, and the high configuration, new exterior, new interior, and new three powers made the Han EV, although a flagship model, the most cost-effective product in BYD’s new energy lineup. Since then, BYD has finally begun to correct the status of its C-end pure electric product line.The second change BYD made after “turning over a new leaf” was to abandon the gearbox and introduce a more powerful generator to drive the mainly serial-connected DM-i plug-in hybrid system. This sacrifice of 4-wheel drive and faster acceleration resulted in significantly reduced fuel consumption, an obvious improvement in the electric driving experience, and a significant decrease in purchase price after subtraction. Since the introduction of the DM-i model, the significantly increased sales of BYD’s plug-in hybrids have already demonstrated a lot.

The third change was the release of BYD’s e3.0 pure electric platform. This marked the beginning of the countdown to the end of BYD’s history of petroleum-to-electric switching. Features such as the 800 V high-voltage platform and double-wishbone front suspension will appear in future BYD models.

In just two short years, BYD has done many correct things, some of which should have been done long ago.

Visible Challenges and Unclear Issues

Yes, with the help of the above “turning over a new leaf,” BYD’s new energy sales this year have achieved unprecedented success. But under an 800 billion market value, BYD needs to prove a lot to the market.

Among the well-known issues such as intelligence, brand image, and sales system, what I want to highlight separately is BYD’s recognition of its own product competitiveness.

We need to see such a phenomenon: Tang EV, with the same generation of battery, three-electric system, the same set of vehicle machines, new interior, larger space, and similar prices, has far less sales volume than Han EV.

What is Han EV’s hot-selling point? What is Han EV’s real competitiveness, and how should BYD create its second hot-selling pure electric vehicle?

If BYD does not have a clear answer to these questions, then the success of Han EV will only be accidental. BYD’s future product lineup will still have to rely on a “having more children makes the fighting better” strategy. The sustainably growing ability of the pure electric product line will also be restricted in the increasingly fierce market competition.

On the other hand, the idea of range-extension and serial hybrid power is not only recognized by BYD, but also by Great Wall Motors and Changan Motors. After the market gap period, how long can the growth of BYD DM-i plug-in hybrids continue?

At present, the answers to these questions are still unknown, and the key to “take off” lies in the sustainability of growth.

Conclusion

Since entering the automobile industry, BYD has experienced several ups and downs, and its current state must be lower than its own expectations.

As one of the most representative players in the domestic new energy competition, BYD started making new energy vehicles in 2008, which shows that it definitely has a vision. However, going from the world’s number one in new energy vehicle sales to gradually being surpassed by Tesla and Volkswagen, BYD must have serious strategic problems.Even standing at today’s node, the fourth largest market value cannot conceal BYD’s insufficient ability to create automotive products. Fortunately, the new energy market is still growing, and the absence of Japanese and German brands in the domestic market of below 200,000 yuan has given BYD sufficient market opportunities and brand recognition. In addition, if the progress of BYD’s battery supply to Tesla goes smoothly, its external battery business is expected to see substantial growth.

In fact, BYD’s strength as the second party has long been reflected in the stable and growing electronic business in recent years. What BYD needs to understand now is how to become their own first party.

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.