Recently, the release of sodium batteries in China has triggered a heated discussion on the constraint of power battery resources. In May, IEA not only published an article on the rapid development of electric vehicles, but also wrote a report “The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions” on resource constraints, in which the importance of resources was highlighted.

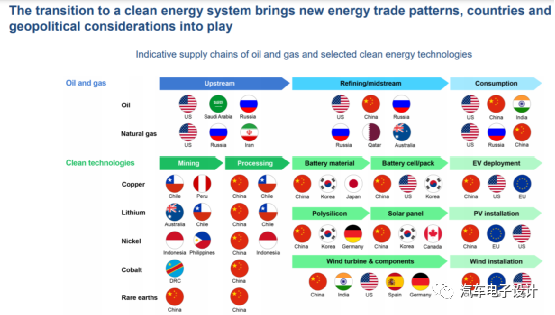

Now Europe and America both want to seize the battery sector, but upstream lithium, nickel, cobalt and rare earths are still restricting the large-scale development of electric vehicles. You can’t really see why the entire Japanese automotive industry is moving towards the development of electric vehicles in the attached image, as there is insufficient resources. While the United States, which is standing firm in petroleum energy, has no presence in the lithium battery resource industry, it is still possible for Australia, Chile, Indonesia and the Philippines to make investments and lay out resources.

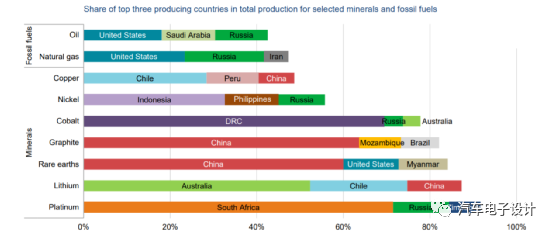

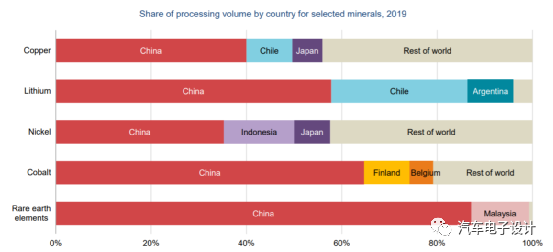

From the perspective of IEA, like the concentration of the petroleum industry in several countries, the supply of key metals related to power batteries is also heavily concentrated in a few countries. Will these countries sit back and raise prices in the future, causing concerns about subsequent supply security for the global development of raw materials for electric vehicles? These new investment projects in key metal mining from discovery to production on average take 16 years, and the timeframe is unlikely to shorten, which will lead to ongoing considerations in the future.

In my understanding, the 10-year subsidies for electric vehicles and China’s position in battery production have enabled China to form a strong upstream resource processing capacity. Although the main target in actual mining is graphite and rare earths, the processing capabilities are comprehensive and high in proportion.

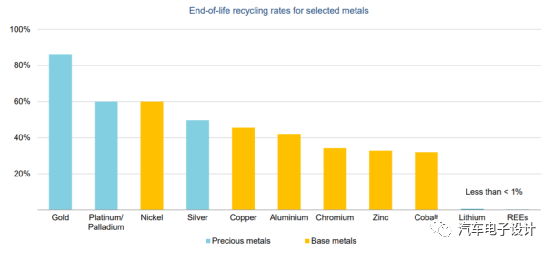

I think the story we are telling is still about the recycling of batteries after they have entered large-scale retirement in the future. However, the recycling rates of nickel and cobalt may still be possible at present, but the price of lithium makes the recovery rate very limited. In other words, our focus regarding lithium resource supply is still mainly on primary resource extraction and supply.

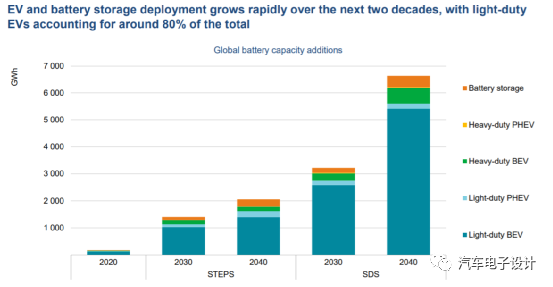

In the most aggressive scenario of IEA’s outlook, there will be a demand of 6 TWh in 2040, and the overall demand and recycling gap will become more significant by then.

In the most aggressive scenario of IEA’s outlook, there will be a demand of 6 TWh in 2040, and the overall demand and recycling gap will become more significant by then.

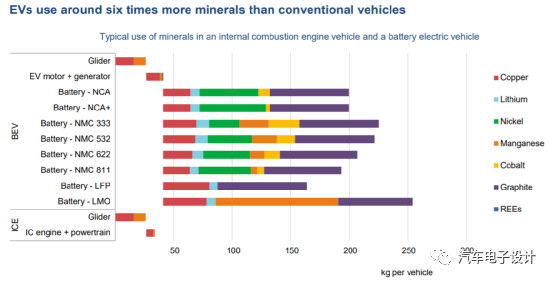

For a single large-capacity electric vehicle, since the demand for battery materials is directly related to weight, which is in units of 200 kg per car, the demand for copper and lithium graphite is not low. The demand for these metals by internal combustion engines is one-sixth less than that of electric vehicles, and the overall demand is based on two major metals: aluminum and steel.

Note: From the perspective of resource constraints, even the 8-series products have too much demand for cobalt.

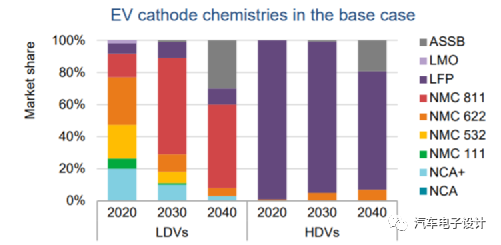

IEA’s judgment is to build heavy-duty vehicles around LFP and passenger vehicles around solid-state batteries and two types of high nickel batteries, as shown in the figure below.

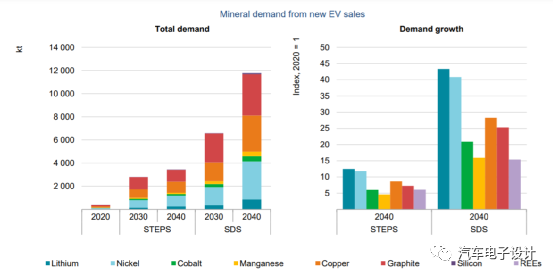

In other words, as decarbonization and electrification work unfold, the demand for battery-related metals is increasing, and multiplied by several times in 2020, due to the overall mining development cycle and resources being concentrated in a few countries, price surges may occur in the later stages, similar to that of new power batteries facing the problem of resource shortages (oil scarcity).

Conclusion

In my personal opinion, the promotion of sodium batteries is more of a hedge against the metal resource shortage estimated by IEA, and the industry is anxious about resource constraints in TWh. However, the investment cycle of upstream mining and the demand for power battery expansion cannot match. If the resource side does not earn money and reduces investment now, the harm in the later stage will be greater. How to balance the development of electric vehicles, the supply of power batteries, and the development of upstream mining is not just a matter of one company, but also a problem that the independent power battery industry chain in Europe and the United States will inevitably consider in the future. In the era of GWh, China has an advantage. In the era of TWh, it is inevitable that various regions will continue to invest heavily, and more companies should participate for better development.

This article is a translation by ChatGPT of a Chinese report from 42HOW. If you have any questions about it, please email bd@42how.com.